WDI Perspective: Segmenting Healthcare to Reach the Poor

Wednesday, April 19, 2017

Should health care be segmented like cars and other products? Pascale Leroueil, Research Manager for Healthcare Delivery at the William Davidson Institute, writes that our gut reaction is likely to be “No!” But what if health care was segmented based on how the care was actually delivered? Originally published on NextBillion.net, an affiliate site of WDI, this article is part of a broader focus on healthcare innovations for the month of April.

The private sector segments populations as a matter of course, producing and marketing products aimed at specific groups of people.

Take automobiles, for example. All function the same way – moving people from one place to another. But different brands and models appeal to specific segments of the population. For those with more money, maybe they would like a luxury sedan or sporty two-seat convertible. For families, maybe it’s a minivan. Or someone with a smaller budget might want an economical car.

But it is not enough to just appeal to a given population. That population must have the resources to buy the car and be willing to forgo other items they could purchase with the money. In the end, while many of us dream about zipping around town in a luxury sports car, most will buy a more practical car that is a good investment and will still provide adequate transportation from point A to point B.

But what about health care? Should health care be segmented in much the same way as cars and other products?

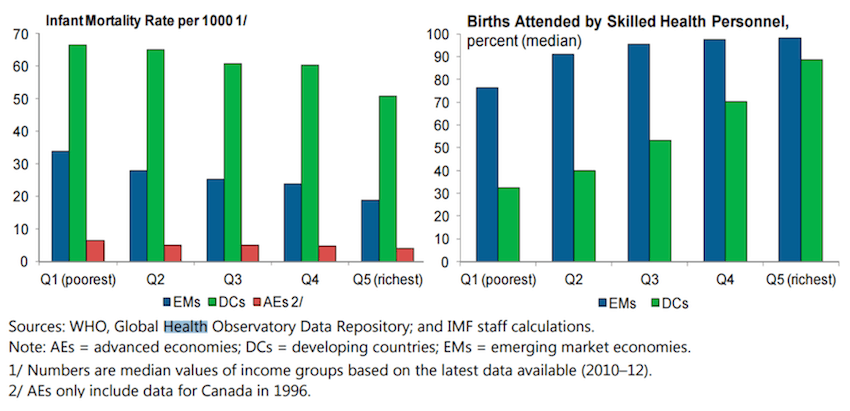

Our gut reaction is likely to be, “No!” After all, it seems unfair that those with money have access to care while the poor don’t. But health care already is segmented across a variety of social determinants, including wealth. In general, the rich have access to a higher quality health care than the poor, and the impact on relative health outcomes is striking. Using infant mortality as a proxy for quality health care, Figure 1 illustrates how there is significant difference in health care quality between rich countries (Advanced Economies – AEs), poorer countries (Developing Countries – DCs) and Emerging Market Economies (EMs). Perhaps more surprisingly, however, is the difference in health care quality within a given set of countries. Whether one is in a rich country or a poor country, health care is segmented such that the relative rich have higher quality care than the relative poor.

But what if health care was not segmented based on the quality of health care provided? Instead, what if health care were segmented based on how the health care was delivered?

This requires distinguishing between what is medically necessary and what is “nice to have.” For example, a patient has a broken leg. For this, the basic package available to everyone regardless of means, might include an X-ray and a cast. A “basic-plus” package for the same broken leg might include – along with the X-ray and cast – a private waiting room with tea-service and a ride home for the patient. The cost of those extras would be borne by the patient.

Similarly, patients could be segmented based on their “willingness to wait.” For example, a mother who needs a wellness check-up for her baby could have the option of scheduling an appointment or coming in for a walk-in visit. In both cases, the mother and baby would be seen by the nurse; the only difference is that the mother with the appointment is guaranteed to be seen at a particular time while the walk-in mother would be seen when the nurse was available. The clinic or hospital could charge the mother with the guaranteed appointment time a premium for that additional “service.”

Even within medically unnecessary services, such as speech therapy and braces, there is the opportunity to segment. An extreme example of this might be plastic surgery done solely for cosmetic reasons. All the the patients could receive the same care during the treatment procedure itself, but some might spend a month recovering inside a resort while others would return home immediately.

While the private sector is more likely to see the value of providing add-on services such as private rooms and guaranteed appointment times, there is nothing inherent to these market-based approaches to prevent the public health sector from doing this as well. Indeed, add-on services could provide additional revenue that could be used to cross-subsidize what they consider their basic package of care. There are already several examples of the cross-subsidization strategy working, including Aravind Eye Center. Those who can afford to pay for cataract surgery at an Aravind clinic receive the care swiftly, while those who cannot must wait until there are enough people who can pay for it. In this way, costs for those who cannot afford to pay are subsidized by those who can.

This market-based approach of giving the rich the equivalent of leather seats when it comes to health care is one way toward making universal health care coverage sustainable.

Image credit: Chris Goldberg/Flickr