WDI’s Scaling Impact Initiative is working with Walmart to chronicle what the retail giant has learned from its efforts to include small producers in global supply chains.

The successes, challenges, and lessons learned will become a policy brief and a teaching case, both written by WDI in collaboration with Professor Linda Scott of Oxford University’s Said Business School. Both documents will be published this spring, and are geared toward Walmart and other retailers looking to develop more effective sourcing programs in the future.

WDI Vice President of Scaling Impact Ted London and Research Manager Colm Fay, along with Scott, are studying two Walmart programs.

One is Empowering Women Together, which sources handicrafts from women-owned base of the pyramid businesses in East Africa, Nepal, India and other emerging markets to sell online. The other is Direct Farm, which buys fresh fruits and vegetables from small- and medium-sized farmers to supply Walmart’s stores in Central and South America, Mexico, South Africa, and India.

The team has interviewed managers from Walmart, the Walmart Foundation, and their implementing partners.

This is the second collaboration between WDI and Walmart. Last year, WDI Publishing released a case study on the evolution of a global cross-sector partnership between Walmart and the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The case looked at what had been gleaned – both positive and negative – during the 15-year collaboration between the two organizations.

The free case, “Walmart and USAID: The Evolution of a Global Cross-Sector Partnership,” focused on partnerships that sought to engage smallholder farmers in the developing world, and highlighted examples from Honduras, Guatemala, Rwanda and Bangladesh. It explored the ways in which these collaborations came about, how they were supported by the partners, and the level of success achieved as measured by Walmart, the Walmart Foundation, and USAID.

The case also identified lessons learned for the future of the Walmart/USAID collaboration, and insights that may apply to the development of public-private partnerships for development more broadly.

In addition, NextBillion’s Kyle Poplin wrote a post on how the case was developed. And Beth Keck, senior director of Women’s Economic Empowerment at Walmart, sat down for a video interview with WDI’s London about the company’s global work.

Image courtesy of Navel Zaveri/Flickr.

Note: This is one in an ongoing series of articles profiling past WDI interns and Multidisciplinary Action Project (MAP) team members and their career paths. Additional profiles in the series may be found here.

With an engineering degree in hand, Patricia Griffin said she was probably destined for a job at an auto plant. But while studying for her MBA at Michigan’s Ross School of Business in 2009, she was part of a WDI-sponsored student team that traveled to a Ugandan hospital.

The experience changed her life – and the course of her career.

As part of the project, Griffin examined Kumi Hospital’s inventory management system and saw that it often ran out of life-saving drugs. She worked with the drug warehouse clerk on some basic supply chain management principles.

“In a matter of seven weeks, the hospital had stopped stocking out of essential medicines and patients stopped dying,” Griffin said. “At that point I realized my skill set was valuable and rare in this part of the world and I could either go back to the auto industry to eke out two seconds of additional productivity on an assembly line or return to Africa and save lives. The right choice was obvious to me.”

After earning her MBA, Griffin took a fellowship with LGT Venture Philanthropy working with Bridge International Academies in Kenya. She also oversaw operations at a nonprofit that partnered with local, smallholder farmers in Kenya to grow trees as a cash crop, and served as an adviser for more than a dozen health entrepreneurs in Kenya and Ethiopia for the global development firm Abt Associates. These work experiences helped Griffin discover where she could best contribute.

In 2014, she started her own company in Kenya – Inagape – that buys fruit from local farmers, dries it, packages it and then sells it as healthy snacks under the name Snak Afya. Its first product is a dried coconut snack food available at Nairobi stores. Plans are to add a flavored coconut snack food and possibly bottled coconut water.

Running her own startup business, Griffin often harkens back to her experience at Kumi Hospital.

As part of the Kumi project, Griffin and three of her fellow MBA students also worked with the staff at Kumi to cut costs so the facility wouldn’t run out of money at the end of each month.

The student team, part of Ross’ Multidisciplinary Action Projects (MAP) for MBA students, divided expenses into four categories – transport, food, medicine and medical supplies.

“We did a deep dive to see how the money was really being spent,” Griffin said. “At the end of seven weeks, we were able to make several recommendations on cost-saving initiatives and even implement some of the ideas.”

One example was that the hospital had two separate pharmacies serving outpatients and inpatients, but only one set of staff that had to walk about 50 yards between both. The hospital wanted to hire a second staff but the MAP team instead created one pharmacy with two service windows. The solution saved the hospital time and money by eliminating the need to hire more staff and making better use of the existing staff’s time.

When Griffin revisited the hospital in 2013, the two-window pharmacy was still in operation. “We’d spent our last weekend in Uganda executing that cost-saving recommendation, so seeing it still intact and functioning was affirming,” she said.

One of the lessons Griffin learned at Kumi was to ask questions and never assume anything. Like, for instance, why two pharmacies?

“I happened to ask why there were two pharmacy rooms in the first place and the answer I received was nothing I could’ve imagined,” Griffin said. “Apparently, during the Ugandan civil war, guerrilla groups would raid the hospital at gunpoint for medicines to treat wounded fighters in the field. When all the medicine was stocked in one room, the entire inventory would be stolen. Cleverly, by separating the pharmacy into two rooms, they’d only lose half their stock.”

That story stayed with her. She also reflects on the advice she received from the late C.K. Prahalad, one of her professors at the time, about working at the base of the pyramid. Prahalad encouraged her to sense an opportunity and then take the leap of faith “with both feet.”

“When the going gets tough and I feel like giving up or throwing in the towel, I think back to the number of sacrifices I’ve made to successfully switch careers,” she said. “I also re-read the encouraging note that Prahalad wrote to me on the bottom of my final essay for his class. It reminds me again why I wanted this career in the first place.”

And she thinks back to the lessons from that WDI MAP experience.

“Questioning my assumptions and taking nothing for granted has become a basic mode of operation for how I conduct my career and life,” Griffin said. “That’s a direct result of the MAP experience.”

Ivana Ulicna of the Pontis Foundation — a partner to WDI’s Education Initiative — weighs in on how integrating virtual (or “training”) companies into education can give Kenyan students the experience and skills necessary to lead their businesses effectively and sustainably.

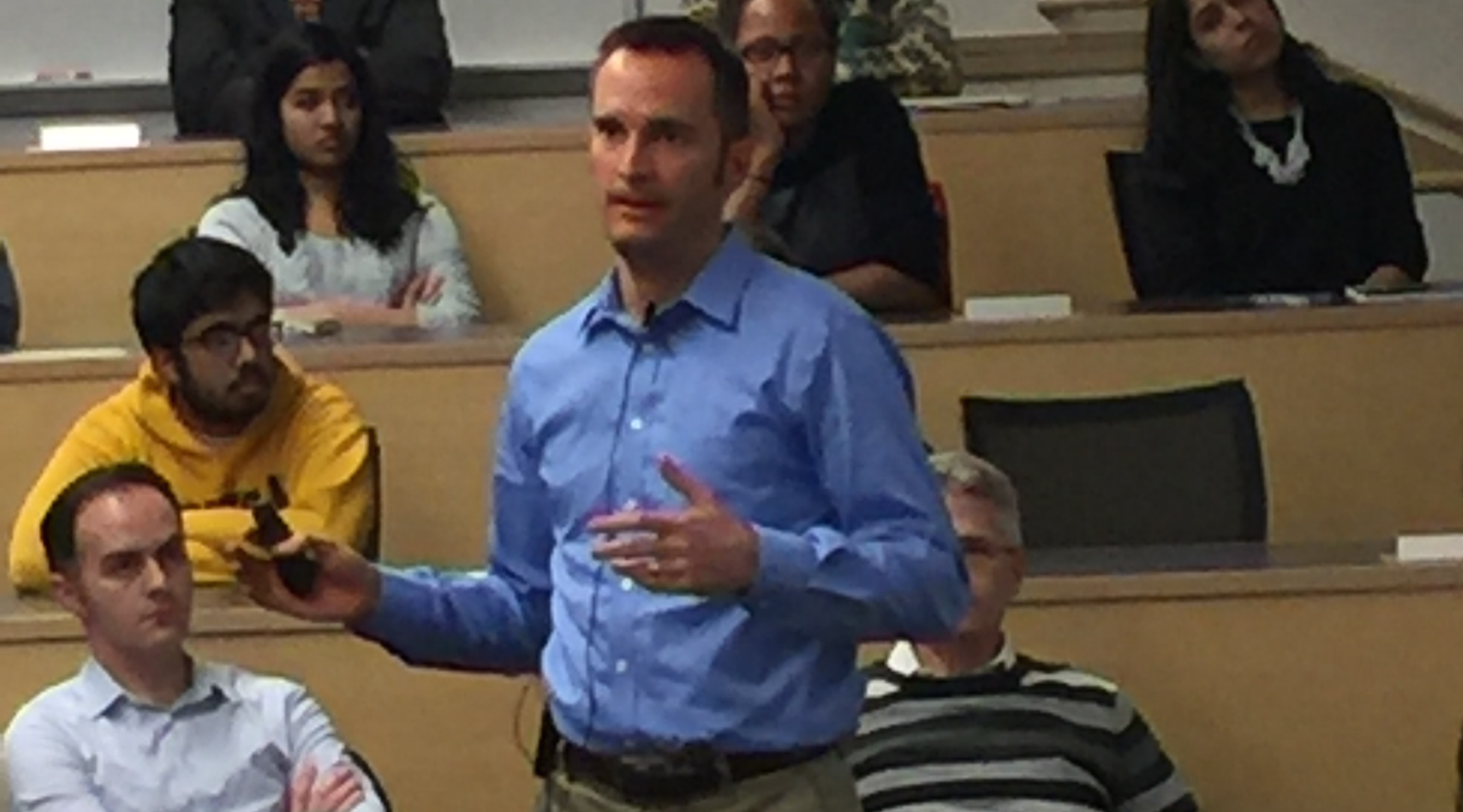

Speaker: Madison Ayer, Executive Chairman, Honey Care Africa Chairman & Co-Founder, Farm Shop.

Supply chains integrating low-income producers and consumers are subject to unique challenges – poor infrastructure, security concerns, informal regulations, and high costs are just a sample of factors. Yet overcoming these barriers can lead to long-term competitive advantage and positive economic impact on communities across the supply chain.

The leader of two ventures in Kenya that serve those living at the base of the pyramid spoke Nov. 18 as part of the WDI Global Impact Speaker Series.

Madison Ayer, executive chairman of Honey Care Africa and co-founder and chairman of Farm Shop, talked about the unique challenges – including poor infrastructure, security concerns, informal regulations, and high costs – of integrating low-income producers and consumers into the supply chain. But, Ayer says, overcoming these barriers can lead to long-term competitive advantage and positive economic impact on communities across the supply chain.

Watch Ayer’s presentation here. Watch Ayer be interviewed by WDI Senior Research Fellow Ted London here.

“Madison is a successful entrepreneur who has turned his focus to base of the pyramid (BoP) markets,” London said. “He launched and subsequently exited two successful IT ventures in the U.S. In BoP markets, he helped turn around Honey Care, and then founded and led the development and growth of Farm Shop.”

Honey Care Africa supplies smallholder farmers with beehives and harvest management services. In addition, it guarantees a market for the beekeeper’s honey at fair trade prices, providing a steady, consistent source of income.

Farm Shop is a social enterprise that serves smallholder farmers across Africa. Farm Shop recruits and trains franchisees that then independently operate community-level agro-dealer shops that supply farmers with all they need to improve production, including seeds, fertilizers, tools and veterinary medicines.

WDI researchers have studied the two ventures in the past. As part of a project, funded by the German development agency GIZ, WDI studied the current landscape of BoP facilitators in the sub-Saharan Africa region. As part of this research, WDI’s Scaling Impact initiative conducted field visits to Ethiopia and Kenya – including the two ventures run by Ayer.

WDI’s Performance Measurement team also conducted a qualitative impact assessment in 2012 to identify the impact of Honey Care Africa on alleviating poverty on children age eight years and younger and developed a case study as part of the series entitled Focusing on the Next Generation: An Exploration of Enterprise Poverty Impacts on Children. The goal of the series, funded by the Bernard Van Leer Foundation, is to gain a greater understanding of the ways in which businesses in emerging markets impact young children’s lives and the potential to optimize impact on children. WDI also wrote and published a popular teaching case study on Honey Care Africa that examined the business’s transition from obligating farmers to maintain their own hives to providing hive management services. The case also explored ways to enhance this new model, including strategies to reduce side selling.

To watch a one-on-one video discussion with Ayer and London, click here.

Inadequate sanitation negatively affects the lives of billions of people in the Base of the Pyramid (BoP) in the developing world, and has a particularly substantial impact on the well-being of millions of young children. Given the magnitude of the challenge and the limitations of existing approaches, enterprise-led approaches to providing public goods are generating growing interest. Emphasizing convergent innovation, enterprises targeting the BoP are presented as potentially sustainable and scalable interventions that generate positive poverty-alleviation effects. Yet our understanding of who is affected, and how, remains limited. To begin to address this gap, we apply a multidimensional framework to an urban-based, sanitation-oriented BoP enterprise, focusing on its poverty-alleviation effects on young children. Our analysis indicates that the enterprise’s effects include changes in capability, economic, and relationship well-being and that these changes can be positive or negative. We also find that the impact varies depending on the role of the stakeholder in the business model and the age of the child. Our results contribute to a better understanding of how to assess the effectiveness of a sanitation intervention and how to evaluate the poverty-alleviation implications of an enterprise-led approach.

This teaching case study examines Honey Care Africa’s transition from obligating farmers to maintain their own hives to providing hive management services. Readers will explore ways to enhance this new model including strategies to reduce side-selling and opportunities to generate greater impacts on farmers’ families, in particular young children.

Case study on the impact of Penda Health on alleviating poverty on children age eight years and younger. Penda Health proves primary care, both curative and preventative, to low- and middle-income families in Kenya while also specializing in women’s health care. The outpatient clinic offers evidence-based, standardized, high- quality primary health care in a friendly environment.

Case study on the impact of Honey Care Africa (HCA) on alleviating poverty on children age eight years and younger. HCA of Kenya supplies smallholder farmers with beehives and harvest management services. In addition, HCA guarantees a market for the beekeeper’s honey at fair trade prices, providing a steady, consistent source of income.

Case study on the impact of Sanergy on alleviating poverty on children age eight years and younger. Sanergy builds 250 USD modular sanitation facilities called Fresh Life Toilets (FLTs) in Mukuru, a large slum in Nairobi, Kenya, and sells them to local entrepreneurs for 50,000 Kenyan shillings (KES) or about 588 USD. Franchisees receive business management and operations training from Sanergy and earn revenues by charging customers 3-5 KES (0.04-0.06 USD) per use.