Building on frameworks developed in other markets, we continued working on the market analysis for a new technology to produce ammonia for fertilizer in a small-scale, distributed way using renewable energy. We have also been assisting the researchers in developing a new company that will take the product to market.

Frank Giustra meets with Acceso Colombia potato farmers in Boyacá, Colombia.

Note: The following interview was originally published on NextBillion.net, which is managed by WDI.

Several months before the COVID-19 crisis began, I reached out to the communications professionals at the Clinton Giustra Enterprise Partnership (CGEP). I had hoped to talk to them about the organization’s spin-off from the Clinton Foundation into what they were now calling Acceso, a new entity focused on building businesses and connecting them to the broader marketplace, particularly in Latin America.

I was pleasantly surprised to be put in contact with Frank Giustra himself, the Canadian businessman and philanthropist who created CGEP through a $100 million donation to the Clinton Foundation. Giustra is a mining financier who also founded Lionsgate Entertainment before turning his attention to philanthropy. (See previous articles about CGEP’s work here and here).

Since that time, the COVID-19 pandemic has put a lot of work on hold. But thanks to the assistance of Acceso’s communications team and to Giustra himself, our interview remained on track. In the following Q&A, he explains Acceso’s new direction as an independent entity, how it is investing directly in small businesses, and several things he’s learned as one of the early financiers in socially focused enterprise development.

Sidenote: Giustra’s connections with the Clinton family have led to some critical press coverage over the years. Whether readers see those topics as legitimate controversies or conspiracy theories, they are not what this interview is about. And as a nonprofit media site that endeavors to avoid politics, we won’t linger on those issues. Still, there are many valid critiques of the role of billionaires in philanthropy and impact investment. To his credit, Giustra fielded my question on the topic.

(Full disclosure: NextBillion’s parent organization, the William Davidson Institute at the University of Michigan, has worked with CGEP in the past. You can read more about that project here.)

Scott Anderson: We began this discussion several weeks before the COVID-19 crisis started. It seems appropriate to first talk about what impact it is having on the work of Acceso and its businesses. How are they adapting?

Frank Giustra

Frank Giustra: Our businesses are a critical source of food for local communities in the countries where we work – in addition to a continual source of income for thousands of farmers. Our businesses have been able to stay open, as we are essential supply chains. Thankfully revenues have not dropped drastically yet, as our supermarket and retail clients have maintained demand; however, there has definitely been a drop in demand from restaurant chains, and we are in the process of assessing how that will impact 2020 results – and any additional funding support we may need.

Where our products are part of broader social or nutrition-based projects (like in Haiti where we supply organizations like Partners in Health and schools, and in Colombia and Venezuela where we supply food kitchens run by ABACO Colombia, World Central Kitchen and Wayuu Taya Foundation with fresh produce to feed Venezuelan refugees) we are doing our best to maintain our deliveries, if not increase them. I’m proud of our team for stepping up to the challenge and working so hard during this difficult time – and our priority is keeping our teams, farmers and supply chains safe.

SA: My impression is that Acceso was structured very differently than many other foundations, particularly for the time when you began building businesses about seven years ago. For one, investments were made directly in agribusinesses that work closely with smallholder farmers and fishers. Can you explain the motivation for establishing the organization in this way?

FG: My mission has always been to find sustainable ways to alleviate poverty. We approached poverty alleviation in two distinct phases during our 12-year history [at CGEP]. During the early years of the organization (2007-2012), we supported multiple health and economic development projects through grant funding and project management. These projects included cataract surgeries, maternal and child nutrition, and farmer training to name a few. We determined that while these projects certainly had impact in their communities, they were not very sustainable because they relied heavily on grant funding; and they were not scalable or replicable as they were fairly unique and targeted to specific communities.

Based on a strategic review of Acceso’s early projects, I felt that we were not doing enough. I really wanted us to have a game changer, something more sustainable and impactful. Beginning in 2012-2013, we decided to test a social business model with the goal of building, investing start-up capital into, and scaling businesses that were replicable. I was prepared to take the early-stage risk and put in the start-up capital to do this. The intention behind building for-profit social businesses is that the profits are meant to be reinvested into the business. Without profits, our work will not be sustainable. Also, until we landed on our current model, I never felt our impact could be substantial enough.

We also decided to build the capacity and expertise of building businesses in-house, so that we could develop a rigorous process, learn from our experience and adapt it to new geographies to become more efficient and successful at replicating. Many impact investors are looking for profitable or close to profitable businesses, but we were prepared to actually build from scratch. Fortunately, looking back on that decision, it seems to have played out well. It hasn’t been easy and there have been a lot of challenges. But in seeing our businesses in El Salvador, Haiti and Colombia firsthand during a trip I made at the beginning of March, I am very impressed with the work our teams have done, and I’m convinced we have a successful model that can be replicated in other countries, either by us or by other organizations.

SA: Acceso seemed to take more of a systems approach in the realm of agribusiness, connecting smaller players to the larger supply chain and distribution channels. In the first few years, what sorts of metrics did you examine to see if you were on the right track?

FG: I’m glad you raise this question, because a systems approach and establishing businesses tailored to market needs are core to our model. We effectively reverse engineer from demand to build our businesses: First, we understand market needs and challenges, and then we assess how we can bridge the gap between the market (large retailers, supermarkets, restaurants and other buyers) and small producers. There are both financial and social metrics that have been key to assessing our impact. On the social impact side, we focused on increasing farmer incomes and creating jobs:

On the financial or commercial side, we look at key metrics like sales and profit with the goal of reaching profitability within five years. Our approach is always market driven. In our early years, we really focused on making sure we had the right product mix and the right clients so that we could grow and scale into local channels/markets. Larger clients typically have higher quality standards, but we knew that they were key to growth, so we monitored farmer production very closely and implemented necessary practices like Good Agricultural Practices training to make sure they were where we needed them to be.

SA: Are there a few success stories that come to mind?

FG: One of our main success stories is our partnership with Super Selectos, El Salvador’s largest supermarket chain, which has more than 100 local stores. With the intention to support economic development in local communities, by partnering with Acceso they were able to increase their local sourcing from less than 10% to more than 50% within a few years. Acceso also grew from becoming a small supplier to their largest supplier by sales and volumes. Both organizations consider this a win-win, as our partnership has created opportunities for local farming communities while also boosting the local economy. We’ve also spoken to multiple farmers who have either moved back from the U.S. or decided not to move to the U.S., as they realized how profitable farming could be. I think it’s incredible that we can help reverse the flow of migration.

SA: There must have been at least some failures. Can you cite a couple and discuss what you learned from them?

FG: I am glad that we had the chance to test different models in different geographies over the past several years. While we’re currently focused on building and managing agribusinesses in Latin America and the Caribbean, we also piloted and built several agribusinesses in Africa and Asia, as well as tested and built inclusive distribution businesses in several countries, and a vocational training business in Colombia. Some of these businesses were more successful than others, and we ultimately decided to focus on the agribusiness model as we had achieved strong proof of concept within a reasonable timeframe, while transferring other successful pilots or businesses to partners.

In our early years of building businesses, we ended up closing one of our agribusinesses because it was a new product which involved a fair amount of uncontrollable risk related to weather and potential crop spoilage. This was a joint decision between us and our buyer/partner. The main lesson we learned is that building successful, profitable businesses is not easy; it takes time and hard work, and even more so when working with low-income populations. Patient capital and the right partners who genuinely care about social impact (beyond public relations), who have “skin in the game,” and who understand the risks of working with small producers and entrepreneurs are supremely important. We also learned from past projects that if we did not assess demand or the market first, all of our work and funding on the supply/farmer side (training, etc.) may not result in high social impact or sustainability.

SA: Philanthropy is facing a good deal of skepticism these days from many sources. There’s been growing concern that philanthropic organizations that are established by billionaires, no matter how well-intentioned, are mainly a salve to social/environmental ills, and that policy makers really should focus on increasing marginal tax rates on high net-worth individuals to pay for more social programs. What is your response to that?

FG: I am not a billionaire and never will be, as I give my money away too fast to ever become one. I personally don’t believe there should be billionaires, period. I would also like to direct readers to a recent article I wrote entitled “Who Wants to be a Billionaire? I Don’t”.

SA: Impact investing has come a long way in the last 13 years. We’ve definitely been witness to a mainstreaming of ESG as well. What do you consider the greatest mark(s) of progress – and what is concerning you on the horizon?

FG: I’ve seen a real change in the world of philanthropy over the last 10-15 years. Donors want to see a return on their giving. They want to see that projects can be sustainable, as opposed to being funded continuously year after year. It’s therefore not surprising to me (and personally encouraging) that impact investing is becoming more mainstream, driven by increased social consciousness. In the last few years, we’re also seeing more and more international non-profits getting into impact investing, which is a sign that organizations are thinking about the sustainability of their work relative to traditional philanthropic models.

One mark of progress we’ve seen is a subset of impact investors who are truly “social first.” This includes some of our partners, such as Acumen in Colombia and Global Partnerships in El Salvador. We’re also seeing collaboration between grant funders and impact investors, particularly in the early stages of a social business – which is critical to de-risk investments, paving the way for later-stage investors. Finally, we have been encouraged by innovative funding models such as Kiva’s crowdfunding program for social enterprises, which our business in El Salvador has benefitted from.

Related to that, an ongoing area of concern is that the funding needs of the “missing middle” (social businesses with funding needs roughly between $100,000 to $2 million) are still largely unmet, particularly in the smallholder agriculture space. Traditional fund structures, including those of some impact investors, are not set up to efficiently deploy capital at those lower ticket sizes, meaning that it is still inherently difficult for many impact investors to be truly social-first. Some investors still believe it’s fairly easy to be profitable early on while solving major issues, and the truth is that businesses working with very poor populations have a whole set of challenges that investors have to understand and factor into their risk tolerance.

SA: Finally, CGEP recently spun off from the Clinton Foundation and established itself as Acceso. Can you explain why this is happening now – and how will Acceso operate with this new structure?

FG: Last year, I made the announcement that I was stepping down from my business interests and would focus the majority of my time on my philanthropy. I love my philanthropic work with all my heart. I consider Acceso my life’s work. I enjoy being hands-on and I get real satisfaction spending time with our beneficiaries. This was the highlight of my trip to our businesses in March: hearing the stories of farmers and employees, and figuring out what opportunities we still have to grow.

In relation to spinning off from the Clinton Foundation, this is an exciting next step and a natural evolution for us. As a builder of social businesses, I believe Acceso’s operating model is suited for an independent organization. I am grateful to the Clinton Foundation for their partnership, and I’m also excited about this new phase as I take on full management of our work. I know our team is excited about this new phase as Acceso as well. Our focus remains building, managing and scaling agribusinesses in Latin America and the Caribbean to sustainably lift farmers and fishers out of poverty, and identifying opportunities for future replication. The day-to-day operations of our local Acceso businesses remain the same, and we are looking forward to expanding our work alongside current partners – as well as increasing our investor base as we have done in the last one to two years. I truly believe we are a leading showcase and success story for social businesses in the agriculture space.

Photos courtesy of Paramo Films / Acceso.

Scott Anderson is communications manager at the William Davidson Institute.

A worker with Chakipi Acceso Peru. Image courtesy of Chakipi.

For over 10 years, the Performance Measurement and Improvement (PMI) team at the William Davidson Institute at the University of Michigan has been using robust monitoring and evaluation approaches to measure results and generate value for businesses and their stakeholders.

Whether we are working with the largest network of micro-distributors in Latin America or a multi-national business in the apparel industry, our goal is to meaningfully engage our partners in the measurement and learning process. We want to make data collection valuable for participants and data findings actionable for decision-makers at all levels of a business, organization or program.

We believe such work should be shared and include practical strategies for applying research to improve performance and generate social impact. That’s why we’ve teamed up with MIT D-Lab to write a Lean Research case study, “Positive Change Through Actionable Metrics.” Lean Research is an approach to improve the practice of data collection involving people and communities in development and humanitarian contexts. (For more information on foundations of the Lean Research approach, check out this three-part blog series on NextBillion.net.

As defined by MIT D-Lab, Lean Research is driven by four principles of good research practice:

Our team’s case study covers how we followed the Lean Research approach and applied each of the four principles to our work with three separate social enterprises. Each of these businesses wanted to strengthen their ability to collect accurate data and lead their own evaluation efforts. As a result of the work, leadership from the three enterprises gained a clearer understanding of how to measure changes in the well-being of the low-income women they work with. They also learned the importance of using both business and social indicators to improve operations.

“Thanks to this process, we were able to review the way we collect data, and create a data collection manual and survey templates for each business model [we have],” said a pilot participant from Chakipi Acceso Peru, one of the businesses in our research.

So far, MIT D-Lab has produced three such cases, which you can find here. Each case describes an example of Lean Research and discusses its results and implications for development work globally. A revised version of the Lean Research Field Guide is expected to be released soon (WDI was a contributor to that work as well!)

We plan to create more cases and practical examples of how the Lean Research framework can be applied. We’re also proud to be able to contribute to what is a robust and growing community of evaluations practitioners. Indeed, we’re always looking to work with businesses that are putting Lean Research at the forefront of their measurement goals.

Want to learn more about the work mentioned in the WDI Lean Research case study? Check out the project description on our website or read the full WDI Impact Report: Positive Change Through Actionable Metrics.

Rebecca Baylor is an Evaluation Consultant with the WDI Performance Measurement and Improvement team.

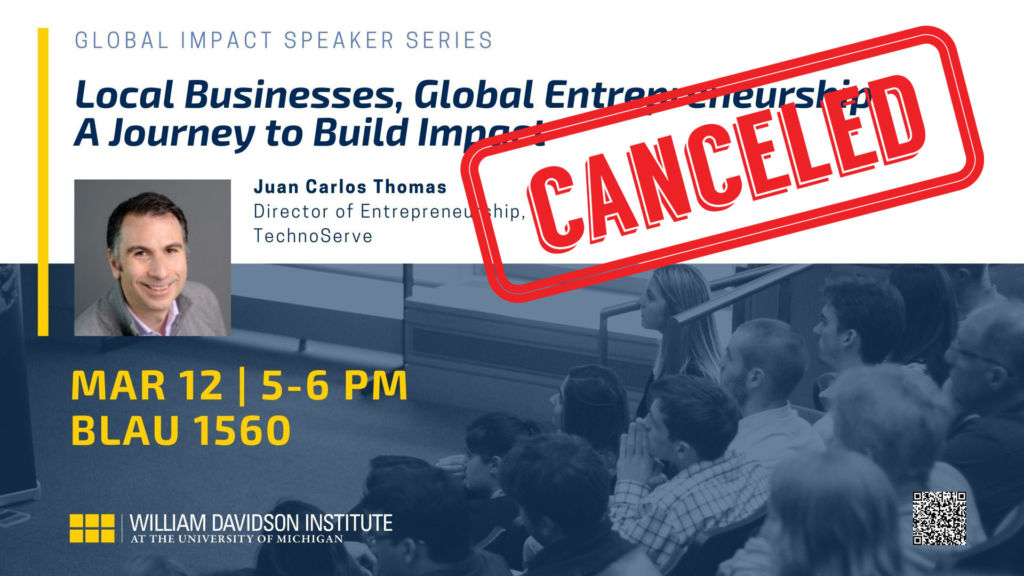

Juan Carlos Thomas, Director of Entrepreneurship at TechnoServe, a nonprofit organization focused on harnessing the power of the private sector to help people lift themselves out of poverty, will be the next WDI Global Impact Speaker. TechnoServe was recently rated the No. 1 nonprofit for reducing poverty by ImpactMatters.

Juan Carlos Thomas

Thomas’s talk, “Local Businesses, Global Entrepreneurship: A Journey to Build Impact,” will explore effective ways to support entrepreneurs and small and growing businesses around the world. It is scheduled for 5-6 p.m., March 12 in Room B1560 (Blau Building) at the University of Michigan’s Ross School of Business. The discussion is free and open to the public.

Thomas leads the development and deployment of best practices in the support of entrepreneurs and small and growing businesses in the organization’s projects. Before assuming his current role, he served as TechnoServe’s Chile Country Director. Among his accomplishments in that role, he led the first inclusive business development program in Chile; the first small business accelerator program in Patagonia; several economic development programs in communities surrounding energy and mining projects; and the design of business development methodologies now being used in Latin America and Africa.

Before opening the TechnoServe office in Chile in 2008, Thomas served as a TechnoServe Fellow. He previously worked in the Corporate Finance and Capital Markets division at Bank Boston Chile. He has lectured on finance, entrepreneurship and social entrepreneurship at various universities. Thomas holds an MBA from INSEAD and a bachelor’s degree from Universidad Adolfo Ibáñez.

With funding support from the Aspen Network of Development Entrepreneurs (ANDE) at the Aspen Institute and Canada’s International Development Research Centre (IDRC), WDI is working with Gente del Futuro (GDF)– a for-profit partnership between three private players within the coffee sector. Together, GDF and WDI are working to collect empowerment data from women working with GDF in Colombia. GDF believes that making coffee more profitable and empowering young people, particularly women, through practical and technical training can promote a more inclusive approach to develop better functioning coffee chains.

To help accomplish this objective, WDI is supporting GDF to pretest and pilot a short quantitative survey that examines how empowerment differs based on women’s role in the coffee value chain. The data will be used to use to inform GDFs operations, in particular how they can better engage and empower women. The survey will be administered to a sub-sample of the 300-500 women that GDF has worked with over the years in Colombia and will assess decision-making and empowerment at home and work.

In winter 2019, WDI sponsored 11 Multidisciplinary Action Project (MAP) teams that worked for organizations around the world. Each team was comprised of four MBA students from the University of Michigan’s Ross School of Business.

One team—Lauren Baum, Nadia Kapper, Paul Mancheski, Jason Yu—spent three weeks in Rwanda working for The Ihangane Project (TIP) to develop a business model to grow a ready-to-use therapeutic food that is used to treat severe, acute malnutrition. Through photos and the words of MAP team member Nadia Kapper, here is the story of the work they did in Rwanda, the impact they had and the memories they made.

The author, left.

This blog was written by 2018 WDI summer intern Nadia Putri, an MBA candidate at the University of Michigan’s Ross School of Business. It originally appeared on NextBillion.net, an initiative of WDI.

By Nadia Putri

In 2012, Lasmini began working as a daily laborer at East Bali Cashews (EBC) and has worked her way up to be the factory’s kitchen production coordinator. Her path was not without obstacles. Many Balinese women at the base of pyramid, especially in a remote village like Karangasem, have limited access to education and employment opportunities. More than 20 percent of women in Karangasem are illiterate. In addition, of those who are employed in the formal sector, the number of women employees are between 50-75 percent of men. Many women stay unemployed at home or work as informal laborers in agriculture, maintaining a small plot of land or a few animals.

Lasmini was one of the few who completed high school. However, lack of opportunity in the village left her unemployed. Her husband’s income alone was not enough for the family. She helped her mom to make and sell canang sari, daily offerings made by Balinese Hindus to thank God in their prayers. But this did not come close to fulfilling their daily needs. Then the opportunity at EBC came along.

EBC is a vertically-integrated social enterprise specializing in cashew products. It operates a processing facility in remote Desa Ban (Ban Village), Karangasem, one of the poorest regions in Bali, Indonesia. In 2012, Aaron Fishman travelled to Karangasem as a health care volunteer. He was amazed by the beauty of the region, but was struck by the poverty of its cashew farmers. He sought out local partners and started EBC, a social enterprise that combines environmentally sustainable business practices with its mission of community development and women’s empowerment.

EBC capitalizes on the opportunity to process cashews domestically in Bali, rather than the more common practice of shipping the raw product overseas for processing. Each day, EBC processes, on average, about 800 pounds of raw cashews, peeling and preparing them for snack production. (This doesn’t include other finished products, which they also package for snack goods). In addition, EBC emphasizes hiring local talent, especially women, because women’s empowerment and economic development are closely related. The factory currently employs more than 400 people, where 80% of them are women from local Karangasem area. The company’s leadership wants to ensure that what they are building in Desa Ban will lead to the community’s overall prosperity.

As a William Davidson Institute MBA summer intern at EBC’s factory, I had the opportunity to interact with many female employees like Lasmini. Some had successfully ascended to supervisory positions, while others have stayed in the same position since their first day. However, one common thread is that they all have benefited from management’s initiatives in providing them with training opportunities.

For instance, Putu started as a cashew-shelling laborer. She only completed elementary school. However, her limited formal education did not discourage her supervisors from training and promoting her to be the first woman mechanic at the EBC factory. I regularly saw her armed with with a toolbox and steel-toed boots, working on machines in need of repairing.

The company also aims to provide equal education opportunity for all levels of employment. For those in the lower level, EBC enrolls employees in NGO-ran weekend classes that prepare them for elementary, middle or high school final examinations, depending on the employee’s needs. For employees who are at staff level or above, EBC offers various in situ training during work hours, ranging from Excel to English.

Providing continuous learning opportunities for employees, in turn, increases their work motivation. As one of the employees told me, “I feel very fortunate to work here and the environment is not like a typical job. Here, it feels like I’m going to college while getting paid at the same time. There’s always something new for me to learn.”

I spent the last two weeks of my internship at EBC providing training and facilitating workshops for supervisors at the factory. Twelve out of 17 training participants were women, some of whom had been recently promoted to supervisor roles, and others who had been supervisors for some time. This shows EBC’s implementation of their women’s empowerment mission: They not only hire women to work as manual laborers, but encourage them to take on leadership roles and further responsibilities.

One example is Wayan, who became coordinator of the peeling area in 2016. Her journey there was not smooth. When her supervisor gauged her interest in becoming a coordinator, she was scared. She had never led people before and felt ashamed of her middle school degree. But, after continuous encouragement, she took on the challenge and has been the area’s coordinator for the past two years.

Wayan’s story shows that leading others often does not come naturally for these employees because they have never had such responsibility before. But EBC keeps pushing the boundaries by providing them with support and setting them up for success once they become a leader. In addition, the company has women in their upper management team, such as General Manager and Head of People Operations, that become role models for the factory employees.

Achieving goals to empower women in a village chock-full of patriarchal tradition is not without hurdles. Though EBC provides opportunities for its employees to grow, at times these opportunities are ignored. In Karangasem, society expects a woman’s first priority should be her family. They fully accept the concept of working mothers. However, this should not come at the expense of their responsibilities at home. After work, many women at EBC will return home and still have to collect hay for their cattle. Some women might turn down promotions or training opportunities due to the additional time commitment. Yet, I’ve heard stories where the household dynamic eventually changed for some of them. Husbands started pitching in to do chores that used to belong solely to women. But such change did not happen overnight. Thus, as EBC work towards fully realizing its goal of equal opportunity for women, its managers need to keep in mind the personal challenges that these employees face everyday. Because once she overcomes these challenges, she can do anything. Lasmini told me once: “I never thought I could get here. But here I am and I can dream again of a better life for my children.”

WDI’s 2018 summer interns before they set off on their voyages.

Over the years, WDI’s summer interns have faced unique challenges as they have conducted their work across the globe for the Institute and its partners. Impassable roads, extreme weather, the occasional wild animal. An active volcano can now be added to the list.

WDI intern Nadia Putri spent her summer in Bali, Indonesia working with East Bali Cashews on quality improvement projects, measuring the company’s impact on women and developing a U.S. market entry strategy. She also got an up close look at emergency preparedness.

“It was really beautiful, but a bit scary at the same time for someone who has never seen anything like it before,” she wrote of watching the sparks of lava and plume of smoke rise from the crater near where she was working. The cashew factory was outside the evacuation zone but management kept a daily eye on the volcano in case conditions changed. Earthquakes in the region have claimed nearly 400 lives during August.

Putri was one of six WDI interns working internationally this summer. Some, like Putri, have returned to the University of Michigan campus; others are finishing up their work and will be back in Ann Arbor soon. While overseas, the interns contributed to a blog to chronicle not only their work but also the experience of living in a foreign land. WDI has highlighted some of the work below and the full blog chronicling interns’ experiences is available here.

East Bali Cashews where Putri worked sources sustainably grown cashews from nearby smallholder farmers and processes them in a factory located in a remote village in one of Bali’s poorest regions. Since its launch in 2012, the company has integrated various social missions in and around its cashew processing operations, including community improvement and women’s empowerment.

Putri, a Ross School of Business MBA candidate, said factory workers were very supportive of her work and willing to explain how the company has impacted them. One employee recalled being hired after graduating from high school and is now in charge of 50 workers.

“At the factory, everyone is very welcoming and open to share their stories,” Putri wrote in her blog. “It’s especially humbling to see such high curiosity and willingness to learn from the factory employees. This serves as my daily reminder that (the) situation you grew up or lived in does not define who you could be.”

In Kenya, Andrea Arathoon, a School of Public Health graduate student, was tasked with helping a local maternity hospital reduce costs and increase patient volumes to achieve sustainability while also maintaining quality. One intervention Arathoon worked on for Jacaranda Maternity is a new outpatient care checklist for prenatal visits.

The checklist is designed to improve patient processing within the outpatient clinic. This improved flow will reduce wait times and result in more efficient consultations, thus increasing patient volume and reducing costs, Arathoon wrote. She ensured the checklist followed the World Health Organization and Kenya Ministry of Health guidelines. The hospital’s doctors, nurses and administrative staff were consulted, and everyone was trained on how to properly use the new tool.

The checklist is designed to improve patient processing within the outpatient clinic. This improved flow will reduce wait times and result in more efficient consultations, thus increasing patient volume and reducing costs, Arathoon wrote. She ensured the checklist followed the World Health Organization and Kenya Ministry of Health guidelines. The hospital’s doctors, nurses and administrative staff were consulted, and everyone was trained on how to properly use the new tool.

“I am very excited about my summer project and the impact that it can have in improving maternity care for women and children in the country,” Arathoon wrote on the blog.

Across Africa on the Atlantic coast, Mason Benjamin is working in Namibia on pharmacy workforce development and hospital pharmacy practice. Benjamin, a College of Pharmacy graduate student, joined a collaborative project between WDI and the International Pharmaceutical Federation Hospital Pharmacy Section. The goal of the project, which includes the University of Namibia School of Pharmacy, is to increase the capacity of hospital pharmacists in Namibia through in-country diagnostics and technical assistance.

Benjamin has been traveling all across the country to visit hospital pharmacies in different regions to develop a landscape analysis of hospital pharmacy practices at both private and public hospitals. Before his site visits began, Benjamin attended the Medication Utilization Review In Africa (MURIA) conference, where he learned about pharmacy practice not only in Namibia but also across Africa.

“I was aware of how different the healthcare system in the United States might be from anywhere else in the world, but always felt that researching other systems online had its limits,” Benjamin wrote in the blog. “I much prefer to learn right from the source and in person, so I was grateful for the opportunity to ask questions to practicing pharmacists from over a dozen different African countries about how things worked in their setting.”

In India, the population of cities is expected to increase by 250 million people in the next 20 years, making employment a crucial need for the new transplants. Ross School of Business MBA student Chris Owen is working with MADE (Michigan Academy for the Development of Entrepreneurs) and its Madurai-based partner Poornatha, which is designing an affordable, world-class coaching curriculum for entrepreneurs in emerging economies. MADE was founded by WDI and U-M’s Zell Lurie Institute.

Owen is identifying best practices of existing coaching programs in India and other emerging economies, conducting a needs assessment of entrepreneurs in Madurai and developing a framework and training curriculum for how coaches will be identified, on-boarded and trained.

“By investing in strong local economies, India can address its dual-challenges of rapid urbanization and rising unemployment,” Owen wrote on the intern blog. “Indeed, for this reason, entrepreneurship in India – and the work of Poornatha – is becoming increasingly important.”

In Brazil, Rebecca Grossman-Kahn – a student at Ross and the U-M Medical School – is developing a tool to assess the social impact of the gender equality programs of Plan International’s Brazil office. Plan International has a long history of advocating for children’s rights but recently decided to focus its work in Brazil on promoting girls’ rights and equality. Gender roles in Brazil tend to be rigid and many girls stop studying in middle or high school to help with housework at home, Grossman-Kahn wrote on the blog. She attended a staff retreat to strategize on how to combat resistance from community members and organizations regarding Plan’s new focus on gender.

In Brazil, Rebecca Grossman-Kahn – a student at Ross and the U-M Medical School – is developing a tool to assess the social impact of the gender equality programs of Plan International’s Brazil office. Plan International has a long history of advocating for children’s rights but recently decided to focus its work in Brazil on promoting girls’ rights and equality. Gender roles in Brazil tend to be rigid and many girls stop studying in middle or high school to help with housework at home, Grossman-Kahn wrote on the blog. She attended a staff retreat to strategize on how to combat resistance from community members and organizations regarding Plan’s new focus on gender.

While at the retreat, a new World Bank report was released that showed girls who complete secondary education can expect to earn twice as much as those with no education.

“Studies like this can help get community leaders on board with Plan’s mission,” Grossman-Kahn wrote.

In Nepal, nearly two out of three working people are farmers. But the country’s rugged topography and lack of infrastructure makes it difficult to farm year-round despite a lengthy monsoon season. Additionally, in rural Nepal, only 5 percent of the population has reliable access to electricity. But the country has more than 300 days of sunshine, making it a perfect candidate for solar-powered agricultural services.

Matthew Carney, a dual degree student at Ross and the U-M School for Environment and Sustainability, spent the summer with the solar startup Ecoprise to help bring solar-powered agricultural services to subsistence farmers in the Terai region of Nepal that borders India. AgroHub, a pay-as-you-go service-based business model recently started by Ecoprise, provides access to solar-powered infrastructure for remote, underserved farming communities. These hubs provide farmers with access to equipment for irrigation, clean drinking water, food-processing and refrigerated post-harvest storage as a service.

Matthew Carney, a dual degree student at Ross and the U-M School for Environment and Sustainability, spent the summer with the solar startup Ecoprise to help bring solar-powered agricultural services to subsistence farmers in the Terai region of Nepal that borders India. AgroHub, a pay-as-you-go service-based business model recently started by Ecoprise, provides access to solar-powered infrastructure for remote, underserved farming communities. These hubs provide farmers with access to equipment for irrigation, clean drinking water, food-processing and refrigerated post-harvest storage as a service.

AgroHub has proved very successful for those farmers who have used it, allowing them to irrigate more land during the winter and monsoon seasons and reducing the use of diesel-powered water pumps that saves money. Carney’s task is to develop a plan to bring the service to farmers in western Nepal.

“Solar-powered agriculture presents an opportunity to raise the living standards of millions of rural Nepali farmers in a sustainable fashion,” he wrote. “It would be a shame to waste it.”

Members of the LIFE project consortium visit a produce stand in Turkey and interviews the owner on how a green grocer sources his produce and his perspective on how he could potentially benefit from the LIFE Food Enterprise Center.

Food can be a powerful means to a more peaceful world because it encourages conversation, cross-cultural engagement and understanding during troubled times, according to the next speaker for the WDI Global Impact Speaker Series.

Johanna Mendelson Forman, a leading voice in the emerging movement of gastrodiplomacy and social gastronomy, will talk about how food can promote social good at her talk, “Can a Hamburger Build World Peace? Lessons on How Food Builds Community One Plate at a Time.” Her talk will be at 5 p.m. on Wednesday, April 4 in Room R2220 at the Ross School of Business. It is free and open to the public.

Mendelson Forman

Mendelson Forman said a revolution is building in which food has become a vehicle for a generation that features chefs as political actors, farmers as champions of environmental sustainability and businesses that have embraced the belief that investment in the entire supply chain is good for business. Young social entrepreneurs are combining food and their business expertise to promote social good with new apps and new inventions. Refugees are learning to cook in their new land in order to gain respect and sow hope.

“Everyone has memories about dishes they ate growing up,” said Kristin Babbie Kelterborn, a WDI senior project manager. “Many times, these recipes have been passed down through generations, giving us a way to feel connected to our culture, bond with others and shape our identity. In many cultures, food is incredibly significant; it is a way of showing hospitality, love and respect.”

“Dr. Mendelson Forman’s presentation will provide insight on what happens when people from different backgrounds share their food cultures with one another. She will talk about a food entrepreneurship project that WDI is currently involved in, which uses food to promote cross-cultural exchange between refugees and host communities in Turkey.”

Under WDI’s Entrepreneurship Development Center, Kelterborn is working on a project, led by the Center for International Private Enterprise and implemented with a consortium of U.S. and Turkey-based partners that aims to develop sustainable livelihoods in the food sector for Syrian refugees and their host communities in Turkey. The project, “Livelihoods Innovation through Food Entrepreneurship,” or LIFE, is establishing Food Enterprise Centers in two Turkish cities to provide business support services to 240 entrepreneurs over two years. The centers will serve as incubators, offering kitchen space and business support services. In addition, the centers will host gastrodiplomacy events using food as a means to promote cross cultural understanding. Mendelson Forman is leading the gastrodiplomacy component of the LIFE project. Sponsored by the US State Department, the consortium includes partners IDEMA (International Development Management), Union Kitchen and The Stimson Center, as well as CIPE and WDI.

Mendelson Forman is an adjunct professor at the School of International Service at American University in Washington, D.C. where she created an interdisciplinary course, Conflict Cuisine®: An Introduction to War and Peace Around the Dinner Table. She is a distinguished fellow at the Stimson Center, where she heads the Food Security Program.

She also has written extensively about food, conflict and Latin America, and has lectured on food-related topics at the Smithsonian Resident Associates Program, Johns Hopkins University Bologna Campus, New York University’s Washington Program and at the United States Pavilion of the 2015 World Expo in Milan, Italy.