Improving reproductive health supply chains to boost access to family planning products in Mozambique. Educating senior managers from around the Baltics. Helping both investors and enterprises they support better measure impact in Latin America. Creating new MBA-level curriculum for universities in Papua New Guinea.

These partner projects are just a few examples of the work WDI performed around the world in 2018. Working with a robust set of private sector and nonprofit partners on a diverse number of projects, WDI effectively applied business skills in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) in impactful ways.

In all, WDI teams worked on more than 40 projects with more than 40 partners in more than 40 countries this past year that focused on our core consulting sectors—education, energy, finance and healthcare, as well as our management education programs, entrepreneurship development, measurement and evaluation services and the deployment of University of Michigan graduate students around the world.

“In 2018, I was impressed by the degree to which the Institute integrated the energy and talents of our staff, University of Michigan students and faculty leaders to address multiple challenges facing for-profit and non-profit organizations,” said WDI President Paul Clyde. “While most of these projects were in one of our key focus areas—Energy, Healthcare, Management education or Finance—many drew on expertise that cut across sectors or disciplines to deliver more complete solutions.”

WDI’s project work leveraged the knowledge and expertise of the Institute’s staff, its research fellows and faculty from the University of Michigan and other world-class higher education institutions to develop business solutions in LMICs. Additionally, WDI disseminated what it learned doing work in the field through published research reports, academic journal articles and notable blog posts. The Institute also contributed to U-M student and faculty enrichment by hosting several compelling speakers at the Ann Arbor campus.

Members of the LIFE project consortium visit a produce stand in Turkey and interviews the owner on how a green grocer sources his produce and his perspective on how he could potentially benefit from the LIFE Food Enterprise Center.

Our work in 2018 spanned the globe and included projects on a wide variety of topics and issues. Among the work, WDI launched a new consulting focus area in the energy sector, connected hundreds of students using virtual technology, developed a model to train nurses for a planned hospital in Ethiopia and trained refugees in the food industry in Turkey. Here are a few highlights from our project work this past year.

Throughout the past year, WDI has widely shared its research and field work a to a broader audience through a number of publications and online journals.

“Participating in the project to test the framework provided us a holistic understanding of poverty. WDI gave us the tools to guide decision-making and track progress towards broader development goals through data collection and analysis.”

—Mónica Varela, director of impact for the Clinton Giustra Enterprise Partnership

WDI intern Nadia Putri (pictured left)

A number of WDI employees penned blogs on their work or trends impacting their research that appeared on the Institute’s website.

In 2018, WDI hosted speakers as part of the the Institute’s Global Impact Speaker Series. While on campus, many of the speakers sat down for one-on-one interviews.

Tom Light, managing director of WaterEquity and a recent guest of the WDI Global Impact Speaker Series, sat down for a one-on-one video interview while on campus. (Watch the discussion below.)

Light, who was interviewed by Pascale Leroueil, vice president of WDI’s Healthcare initiative, talked about a number of aspects of WaterEquity, which is the first-ever impact investment management firm with an exclusive focus on ending the global water crisis. Those included how the organization operates, how blended finance fits into the strategy, the biggest advantage to working with the private sector and where Light sees WaterEquity in 10 years.

WaterEquity’s experience in water and sanitation investment opportunities in low- and middle-income countries guide its investment strategies that drive both sustainable financial returns and social impact. By investing in enterprises operating in impoverished communities, WaterEquity’s investments help these enterprises scale up, meet increasing market demand and deliver universal access to clean, safe water and sanitation, the fund notes.

WaterEquity was established by Water.org, the charity co-founded by actor Matt Damon, to mobilize capital for water and sanitation enterprises serving the needs of poor people. Last month, WaterEquity announced the first close of its US $50 million flagship fund—WaterCredit Investment Fund 3 (WCIF3)—at US $33 million. Investors included Bank of America, the Overseas Private Investment Corporation (OPIC), Ceniarth LLC, Niagara Bottling, as well as the Conrad N. Hilton, Skoll, and Osprey Foundations. A second-close is projected before the end of the year.

Light oversees all aspects of the business including strategy, operations and expansion. He has more than 18 years of experience in public and private capital markets in the areas of investment management, investment banking and fund development. Previously, Light led Grameen Foundation’s impact investing strategy serving first as a fund manager and then as the Head of the Capital Management & Advisory Center.

He received his B.A with honors from the University of Michigan in Quantitative Economics, holds an MBA in Finance from the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania and is a chartered financial analyst.

By Colm Fay

In early September in Delhi, India, the William Davidson Institute at the University of Michigan, and Miller Center for Social Entrepreneurship at Santa Clara University launched “Closing the Circuit: Accelerating Clean Energy Investment in India.” The event included round-table discussions with enterprises and investors on how they might implement some of the ideas presented in the paper.

One theme that emerged is that the challenges facing enterprises in the clean energy industry in India and the lessons they are learning are not unique to either the clean energy industry or, indeed, to India. In fact, some of the findings from our research reflect patterns that can be observed in any nascent industry. While the context of providing access to energy in India has its own unique characteristics, what we know about how industries develop might help guide investment and provide some clues as to what might come next.

After interviewing several energy access enterprises in the Energy Access India (EAI) program – funded by USAID from 2015-18 and implemented by Miller Center and New Ventures India – we observed a pattern emerging in terms of how enterprises evolved. There were three distinct stages of development: an early initial focus on a compelling value proposition; a stage of vertical integration where a company takes on additional supporting activities; and, a stage of moving these activities outside the enterprise through outsourcing partnerships to specialize around the enterprise’s core competencies.

In the “early focus” stage, enterprises develop a value proposition that targets a specific pain point for a specific customer segment. Hopefully they’ve co-created this value proposition with those customers, and it is something that creates value for them. Enterprises will likely see some early success as the product precisely meets the needs of these customers and they have the ability and willingness to pay for it.

Once enterprises seek to grow beyond this stage, they may be addressing a different customer segment, or operating in different geographic regions where the value proposition they’ve developed doesn’t fit quite as well. This may require widening their offering, through the addition of a consumer financing facility, developing new distribution models, additional after-sales service, etc. In a developed industry, partners would exist to undertake these activities. However, in nascent industries such as the clean energy industry in India, these partners often don’t exist, and enterprises must do it themselves.

It’s helpful to understand why these partners may not exist in the early stages of an industry’s development. Providing inputs or services in these contexts often require the creation of “specific assets” – investments that have extremely limited and specific uses. For example, if there is only one vendor of household appliances serving a particular region of rural India, developing an entirely new distribution network for household appliances as a standalone business is unlikely to be a profitable business. At the price that the distributor would have to charge to cover their cost, it would be cheaper for the vendor to build this capability themselves.

However, enterprises often can’t continue to be experts in everything as they grow. For most enterprises, the next stage of growth is going to require focusing on their core competencies, executing at higher volumes that generate economies of scale and having partners optimized around providing inputs or supporting services. If the enterprise has been successful in demonstrating the possibility for commercial viability, it is possible that others have recognized the opportunity and have entered the market. Now providers of supporting inputs and services look at the market and see multiple potential clients and that mitigates the risk of their investments.

Simpa Networks is a great example of this type of evolution. The enterprise started out as a provider of solar home systems. As it developed its distribution network, it launched consumer financing products that enabled a greater number of customers to purchase the product. It also began providing a range of appliances that increased the use of energy, thereby increasing demand for its core product. Through this process, the enterprise has become an expert in understanding consumer needs and providing solutions to meet these needs through an extensive distribution network that reaches the last mile. Rather than replicating this integrated model everywhere, it now seeks to optimize its strategy around this core competency to become the leading distributor of household appliances to the last mile regardless of where the energy to power them comes from. In effect Simpa Networks is outsourcing the electricity generation component of its business. This kind of specialization only becomes possible when there is a sufficient number of energy providers in the market. Because they are focused only on electricity generation, and are serving smaller geographic areas, they are able to do so more efficiently than Simpa Networks can. This demonstrates another interesting twist – what may have been the subject of an enterprise’s early focus may not continue to be its core competency as it grows.

This evolution from early focus to vertical integration to specialization is nothing new. It is exactly how firms operate in nascent industries. While these models can provide guidance for enterprises and help inform their strategies, it is also important for impact investors and the development community to recognize these dynamics of how an industry matures. It can be tempting for these stakeholders to focus on finding the next new technology, the next business model innovation, or a new financing vehicle that will unlock sustainability and scale. What isn’t as obvious is investing in business to business enterprises across the value chain that facilitates specialization and optimization or improvements in the legal environment that make it easier to enforce contracts between partners. In our discussions with investors in the clean energy space in India, we noted that several are beginning to look at whether their investments are catalytic for the industry, as well as representing good investment deals.

This was a topic of a number of conversations at SOCAP 2018 in San Francisco in October. As part of the panel discussion “Moving from Good Impact Deals to Great Systems Change,” Clara Miller of the Heron Foundation described the importance of supporting efforts like the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board. Neil Yeoh of Echoing Green encouraged investors that wish to see greater pipeline, to also invest in the plumbing.

In “Closing the Circuit,” we also identify some broad categorizations of the Energy Access India (EAI) portfolio companies in terms of the business models they are pursuing. While the distinction between business models may be fuzzy, we saw three distinct patterns emerge; pure-play energy providers, complementary products and services and integrated productive use.

Pure-play energy providers are focused on the generation of electrons at volumes that are profitable. This may mean providing a combination of solar home systems, rooftop solar and solar pumps. These companies leverage economies of scale across these different customer segments to reduce costs and become commercially viable. For example, Argo Solar provides rooftop solutions for profitable customer segments including commercial and industrial customers. It also engages in government tenders for solar pumps in rural markets and drives economies of scale across both markets.

Complementary products and services enterprises focus on developing a basket of products, which may include both the generation and use of electrons. These companies leverage economies of scope to reduce costs and become commercially viable. This means that production of a second product can be done so more efficiently because the company is also producing the first product. Grassroots Energy (GRE), for example, is a biogas production company in the EAI portfolio. It uses animal waste to produce gas that is used as a backup energy source for mini-grids rather than diesel generators. To do this it needs to collect animal waste from local farmers. The residue that remains after the production of biogas, with some addition of nutrients, is an effective fertilizer. GRE can produce this fertilizer product much more efficiently than a standalone business because it already collects the waste and processes it through bio-digestion in the course of generating energy.

Integrated productive use enterprises provide access to energy, but also focus on promoting and facilitating productive use of that energy. This is typically required in contexts where ability to pay is low, and productive use of energy has economic benefits that increase customers’ ability to pay. Without productive use to drive up utilization of the energy generation assets, typically mini-grids, these businesses would not be viable. These models require deep learning about how such communities operate, their energy needs, and how to identify and nurture productive use applications. Companies implementing this model leverage economies of learning to reduce the cost of each subsequent implementation.

Mlinda is an example of this model. It installs mini-grids that provide a higher-quality and more reliable source of energy for rural communities in Jharkhand, India. It also invests significant effort in helping the local community to develop micro-enterprises, such as producing mustard oil, rice hulling and poultry production. Of course, this is only economically productive if there is a market, and so Mlinda also creates market linkages to enable the community to sell these products. As it replicates this model, Mlinda is developing the knowledge assets that will enable it to reduce the cost of community engagement over time.

These models and the associated economies of scale, scope, and learning might sound familiar to anyone who has taken an MBA strategy class. Hagel and Singer cover similar ideas in “Unbundling the Corporation.”

We spend a lot of time focusing on the unique aspects of working in resource constrained environments. Indeed, it is critically important to understand the inherent nuances. However, these examples demonstrate that despite the vast differences in context, some of the business principles we are familiar with in other industries can be observed and that creates the possibility that we might be able to look to history, and to other industries, to anticipate what might happen next in these markets. Further, it may help entrepreneurs, investors, funders and practitioners to gain a deeper understanding of what they should do next to help accelerate these industries to a point where they are mature, competitive and can attract sufficient commercial capital to become self-sustaining.

Colm Fay is a program manager leading WDI’s Energy Sector focus area.

Download PDF of the report

The author, left.

This blog was written by 2018 WDI summer intern Nadia Putri, an MBA candidate at the University of Michigan’s Ross School of Business. It originally appeared on NextBillion.net, an initiative of WDI.

By Nadia Putri

In 2012, Lasmini began working as a daily laborer at East Bali Cashews (EBC) and has worked her way up to be the factory’s kitchen production coordinator. Her path was not without obstacles. Many Balinese women at the base of pyramid, especially in a remote village like Karangasem, have limited access to education and employment opportunities. More than 20 percent of women in Karangasem are illiterate. In addition, of those who are employed in the formal sector, the number of women employees are between 50-75 percent of men. Many women stay unemployed at home or work as informal laborers in agriculture, maintaining a small plot of land or a few animals.

Lasmini was one of the few who completed high school. However, lack of opportunity in the village left her unemployed. Her husband’s income alone was not enough for the family. She helped her mom to make and sell canang sari, daily offerings made by Balinese Hindus to thank God in their prayers. But this did not come close to fulfilling their daily needs. Then the opportunity at EBC came along.

EBC is a vertically-integrated social enterprise specializing in cashew products. It operates a processing facility in remote Desa Ban (Ban Village), Karangasem, one of the poorest regions in Bali, Indonesia. In 2012, Aaron Fishman travelled to Karangasem as a health care volunteer. He was amazed by the beauty of the region, but was struck by the poverty of its cashew farmers. He sought out local partners and started EBC, a social enterprise that combines environmentally sustainable business practices with its mission of community development and women’s empowerment.

EBC capitalizes on the opportunity to process cashews domestically in Bali, rather than the more common practice of shipping the raw product overseas for processing. Each day, EBC processes, on average, about 800 pounds of raw cashews, peeling and preparing them for snack production. (This doesn’t include other finished products, which they also package for snack goods). In addition, EBC emphasizes hiring local talent, especially women, because women’s empowerment and economic development are closely related. The factory currently employs more than 400 people, where 80% of them are women from local Karangasem area. The company’s leadership wants to ensure that what they are building in Desa Ban will lead to the community’s overall prosperity.

As a William Davidson Institute MBA summer intern at EBC’s factory, I had the opportunity to interact with many female employees like Lasmini. Some had successfully ascended to supervisory positions, while others have stayed in the same position since their first day. However, one common thread is that they all have benefited from management’s initiatives in providing them with training opportunities.

For instance, Putu started as a cashew-shelling laborer. She only completed elementary school. However, her limited formal education did not discourage her supervisors from training and promoting her to be the first woman mechanic at the EBC factory. I regularly saw her armed with with a toolbox and steel-toed boots, working on machines in need of repairing.

The company also aims to provide equal education opportunity for all levels of employment. For those in the lower level, EBC enrolls employees in NGO-ran weekend classes that prepare them for elementary, middle or high school final examinations, depending on the employee’s needs. For employees who are at staff level or above, EBC offers various in situ training during work hours, ranging from Excel to English.

Providing continuous learning opportunities for employees, in turn, increases their work motivation. As one of the employees told me, “I feel very fortunate to work here and the environment is not like a typical job. Here, it feels like I’m going to college while getting paid at the same time. There’s always something new for me to learn.”

I spent the last two weeks of my internship at EBC providing training and facilitating workshops for supervisors at the factory. Twelve out of 17 training participants were women, some of whom had been recently promoted to supervisor roles, and others who had been supervisors for some time. This shows EBC’s implementation of their women’s empowerment mission: They not only hire women to work as manual laborers, but encourage them to take on leadership roles and further responsibilities.

One example is Wayan, who became coordinator of the peeling area in 2016. Her journey there was not smooth. When her supervisor gauged her interest in becoming a coordinator, she was scared. She had never led people before and felt ashamed of her middle school degree. But, after continuous encouragement, she took on the challenge and has been the area’s coordinator for the past two years.

Wayan’s story shows that leading others often does not come naturally for these employees because they have never had such responsibility before. But EBC keeps pushing the boundaries by providing them with support and setting them up for success once they become a leader. In addition, the company has women in their upper management team, such as General Manager and Head of People Operations, that become role models for the factory employees.

Achieving goals to empower women in a village chock-full of patriarchal tradition is not without hurdles. Though EBC provides opportunities for its employees to grow, at times these opportunities are ignored. In Karangasem, society expects a woman’s first priority should be her family. They fully accept the concept of working mothers. However, this should not come at the expense of their responsibilities at home. After work, many women at EBC will return home and still have to collect hay for their cattle. Some women might turn down promotions or training opportunities due to the additional time commitment. Yet, I’ve heard stories where the household dynamic eventually changed for some of them. Husbands started pitching in to do chores that used to belong solely to women. But such change did not happen overnight. Thus, as EBC work towards fully realizing its goal of equal opportunity for women, its managers need to keep in mind the personal challenges that these employees face everyday. Because once she overcomes these challenges, she can do anything. Lasmini told me once: “I never thought I could get here. But here I am and I can dream again of a better life for my children.”

Note: This article originally appeared on PYXERA Global. It is re-published here with permission.

In 2017, the William Davidson Institute at the University of Michigan collaborated with the Global Alliance for Clean Cookstoves (the Alliance) to assess the lessons learned so far on the Alliance’s journey to accelerate the clean cookstove industry. This blog is based on the article “Accelerating an Impact Industry: Lessons from Clean Cookstoves” first published by the Stanford Social Innovation Review on June 1, 2018.

Announcing the launch of the Alliance in 2010 at the Clinton Global Initiative, then Secretary of State Hillary Clinton remarked that the Alliance would “work toward the goal of 100 million homes adopting new clean stoves and fuels by 2020. Our long-term goal is universal adoption all over the world.” By bringing together leaders from both the public and private sectors, the Alliance aimed to build a clean cookstove industry that could deliver this vision.

For decades, the development community has been investing in programs that seek to harness the power of business to address social challenges. Not only has this meant investing in private enterprises, but also investing in developing the policies, information, institutions and infrastructure that define the industries in which these enterprises operate—what we call impact industries.

Of course, before the Alliance launched there were many efforts to invest in the clean cookstove industry. But like many impact industries, these were fragmented efforts that operated independently of each other and lacked an integrated vision. This resulted in a lack of investment and coordination, and market environments that make it challenging for enterprises to be profitable – never mind reach scale. Rather than being another independent effort, the Alliance was formed to be what we term an Impact Industry Accelerator (IIA)—an entity charged with catalyzing an entire impact industry.

Almost three billion people around the world still cook over open fires or with biomass such as wood, charcoal and dried animal dung. The stoves they use are inefficient, and they expose the user to a variety of toxic gases, chemicals and airborne particulates. These pollutants cause a variety of health issues, including pneumonia and heart disease, and disproportionately impact women and girls who do most of the cooking. Apart from the health impacts, these inefficient stoves and biomass fuels have impacts on climate change and the environment.

The Alliance aims to better understand the links between improved cooking technologies, and changes in these negative outcomes. It works globally to advocate for improved standards for cookstoves and fuels, to promote investment in enterprises that provide them, and to educate and inform consumers about their benefits. At the country level, it works with local governments, non-governmental organizations and the private sector to develop and execute plans to achieve these objectives.

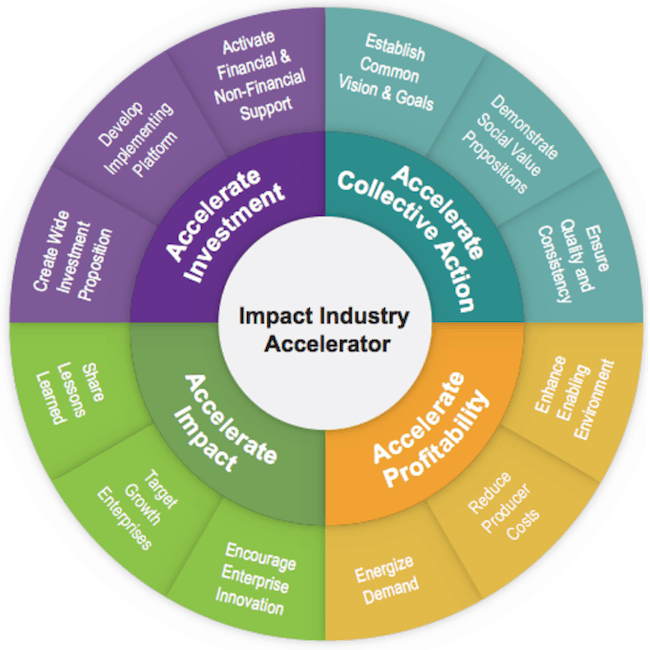

For this research we interviewed Alliance staff and partners in Washington, D.C., Kenya and Bangladesh. In these discussions we talked about what the Alliance has done to accelerate the clean cookstove industry, but also things that the Alliance and other organizations have not addressed yet. This led us to identify four different, but interconnected stages of impact industry acceleration—accelerating investment, collective action, profitability and impact. The Alliance didn’t implement these strategies sequentially, as there were overlaps and iterations. Indeed, the Alliance found itself investing in activities from all four stages at any given time, albeit at different intensities.

Four Acceleration Strategies for the Clean Cookstove Industry

1. Accelerate Investment

The Alliance did three key things to mobilize resources for the clean cookstove industry:

2. Accelerate Collective Action

Given the multitude of prior and current efforts to develop the clean cookstove industry, the Alliance had an important part to play in coordinating a collective strategy for action:

3. Accelerate Profitability

The Alliance aimed to increase access to clean cookstoves and fuels through healthy markets, and has done three important things to help enterprises achieve profitability:

4. Accelerate Impact

To increase impact and scale, the Alliance has focused on key steps to encourage innovation, scale and learning:

By 2017, the Alliance had experienced important successes in accelerating investment and collective action, and its efforts focused on this latter stage. As it looked to the future, it sought to place greater emphasis on accelerating profitability and impact, and on the creation of a healthy market for clean cookstoves and fuels. However, this shift will likely require new thinking in terms of internal capabilities, as well as new external partnerships. This framework provides a roadmap for that transition.

While we developed this framework and roadmap for the Alliance, we think these principles can be of benefit to other IIAs in similar impact industries. Frameworks such as these can facilitate improved strategies and approaches that increase the probability that IIAs can turn their visions of impact into reality.

This article is part of a series on “solvable problems” within the context of the UN Sustainable Development Goals. The Global Engagement Forum: Live takes place this October 10–11, 2018, bringing together leaders from across the private, public, and social sectors to co-create solutions and partnerships to address four urgent, yet solvable problems—closing the skills gap in STEM, reducing post-harvest food loss, ending energy poverty, and eliminating marine debris and ocean plastics. Learn more about the Forum here.

Image courtesy of Russ Keyte.

Ecozen Solutions, which has developed a solar powered cold storage system, is a company that participated in the research project. (Image courtesy of Ecozen Solutions)

WDI and the Miller Center for Social Entrepreneurship at Santa Clara University will mark the release of a new paper exploring what enterprises and investors have learned about energy access in India with an event on Sept. 6 in Delhi.

The paper, “Closing the Circuit: Accelerating Clean Energy Investment in India,” is based on the experiences of enterprises and investors involved in the Energy Access India (EAI) program. EAI is a three-year, USAID-funded program intended to narrow the gap between clean energy enterprises and investors. The program provides access to knowledge and mentorship that boosts enterprises’ investor readiness and by facilitating more funding to these enterprises.

A Freyr Energy solar plant in India, one of the companies included in the research. (Image courtesy of Freyr.)

EAI program’s broader goal is to provide energy access to some of the approximately 300 million people in India who lack access by helping private energy enterprises develop innovative business models to achieve sustainability at scale. The program provided acceleration services to 26 energy enterprises in the country that represent a range of technologies and business models. The enterprises have achieved varying levels of success in growth, impact, and financial sustainability.

“Our collaboration with WDI helped discern key lessons from accompanying over 30 social enterprises focused on clean energy access,” said Thane Kreiner, executive director of Miller Center for Social Entrepreneurship. ”We hope this report will help clean energy enterprises connect with impact investors who want to increase energy access for India’s poorest people, and thereby transform their lives.”

The paper highlights opportunities for greater alignment between enterprises and investors. It also:

WDI’s Colm Fay, who heads the Institute’s Energy initiative and is lead author on the paper, said the Sept. 6 discussion at the Royal Plaza hotel in New Delhi will focus on what the EAI enterprises have learned about how to develop commercially viable models and strategies, as well as what patterns are emerging. Attendees will also talk about some of the paper’s recommendations to spur discussion.

“We’re hoping that the event attendees can take the recommendations we’ve developed in the paper, and determine the resources and partnerships required to put them into action, and the next steps to get there,” Fay said.

The research and subsequent paper on the EAI program is the first project of WDI’s fledgling Energy initiative. Fay said there are other current projects with graduate students at U-M’s School for Environment and Sustainability, U-M’s Erb Institute for Global Sustainable Enterprise and with faculty across the U-M campus.

The research and subsequent paper on the EAI program is the first project of WDI’s fledgling Energy initiative. Fay said there are other current projects with graduate students at U-M’s School for Environment and Sustainability, U-M’s Erb Institute for Global Sustainable Enterprise and with faculty across the U-M campus.

The initiative works with individuals and enterprises that are developing innovative approaches to power generation, and connects them with the expertise, knowledge, and tools to design commercially viable business models and build profitable enterprises. WDI’s Energy initiative works with University of Michigan faculty, students and other collaborators to increase access to energy in low- and middle-income countries, and to develop innovative models or technologies that can reduce reliance on non-renewable energy sources.

“Our goal with the Energy Initiative is to combine the technical expertise we have access to across the U-M campus, with WDI’s experience in business model innovation in emerging markets to support the development of enterprises that are commercially viable, while also increasing access to renewable energy,” Fay said.

By Dan DeValve

The decision by small and medium enterprises (SMEs) in emerging economies to enter an international market is a key step in their maturation. For some SMEs, the move is necessary for survival in a competitive local economy, while for others it’s a logical next step for a successful and growing organization.

Kim Ian’s Dairy Delights is an excellent example of how a locally successful business in an emerging economy, in this case, the Philippines, approaches the decision to transition to the regional or international market. In 2015, I traveled to the Philippines and visited the town of Los Baños, home to many agribusinesses and located near the capital city of Manila. One of the town’s successful small businesses, Kim Ian’s Dairy Delights, had rapidly grown its production of goat milk-based cream cheese. It now faced a decision between scaling up the business to reach supermarket chains in Manila, or remaining in the much smaller niche market in Los Baños. The business owner recognized that expansion of the business would require reallocation of resources to pay for marketing and logistics, significant financial investment and risk, and a strategy for healthy growth of the company. Despite the risks, ultimately the namesake owner decided that their success hinged on a transition to the larger Manila market.

“Foreign market entry is considered as a key strategy to grow and survive over longer periods of time for SMEs,” according to a recent study on Bangladeshi SMEs in the International Marketing Review. In emerging economies with vibrant entrepreneurship sectors, such as the Philippines, the decisions made by these business leaders are instructive and can be illuminating for SMEs in other emerging economies.

While entering the export market has clear benefits, it is a major risk for a small business and can easily result in failure. As key factors of success, a recent study in the Journal of World Business stressed the importance of international business experience on the part of the SME owner, the strength of the home country’s institutional support for SMEs, and whether the SME is using the proper business model. If they have the advantage of institutional support, such as the local government or a business incubator, business owners can also utilize a “learning-by-exporting” model to make the transition, as highlighted in a previous NextBillion post.

A selection of three recent case studies published by WDI Publishing, part of the William Davidson Institute, highlights several issues commonly faced by Philippine SME owners as they consider a move to the international market. These three cases, which are available for free, were among a total of 94 published as part of a four-year project focused on training university faculty in the Philippines on how to teach and write business case studies. WDI implemented the project, in partnership with RTI International and the United States Agency for International Development (USAID).

A business case study is a documented analysis of a real-life business scenario, typically one in which the protagonist must make a crucial decision affecting the success of the business. As a teaching tool, cases provide students with “real-life” experience in decision-making and strategic thinking. As Philippine faculty engaged with a local business and identified a dilemma to feature in their cases, we noticed many focused on whether or not SMEs in the Philippines should enter international markets.

A common theme runs across these three cases. Each business is established in the domestic market with varying degrees of success, and each owner recognizes the advantages to be gained in exporting. Despite the potential benefits, the business owners must also consider the risks, especially adjusting an existing business model and scaling up production capacity to meet the demands of a new market.

Because the case studies were published in 2016 and 2017, WDI was able to review the various decisions ultimately made by these business owners and the ensuing results:

As this view inside three organizations showcases, SME owners can find it difficult to make the transition from domestic to international markets due to a lack of business experience. However, as illustrated in the cases of IPMC and REFMAD, government support for SMEs during this process is crucial. It can include assistance, such as the coordinating of trade fairs to help business owners make new connections, entrepreneurship training programs to provide business owners with the tools needed to scale a business, or even simple promotion of the business to potential customers.

As in the case of GFCP, if the business expertise, proper business model and ability to scale up production are absent, and the business has little to no external support, the idea of entering the international market remains only a dream.

Note: This article was written by Daniel DeValve, a senior project manager for grants management at WDI. The article originally appeared on NextBillion, which is managed by WDI.

Photo by I Travel Philippines via Flickr

A case study by a Rutgers Business School professor about a start-up enterprise in Pakistan and its quest to be self-sustaining after 12 months has won first place in the WDI 25th Anniversary Case Competition.

“Roshni Rides: Pricing Transportation for the Underserved,” by Can Uslay examined how the enterprise, which provides affordable, dignified transportation to refugees and was awarded the $1 million Hult Prize in 2017, dealt with many challenges as it prepared to launch. For the case, Uslay followed the Roshni Rides team as it tried to find a price point that made it affordable to its customers while also generating enough money to make future expansion possible.

“Roshni Rides wants to restore the dignity of refugees by providing accessible, affordable, and reliable transportation, one ride at a time,” Uslay said. “For me, it was great to be able to create a case study to convey their powerful story which will resonate with more people as a result of this win.”

The case competition celebrated and commemorated WDI’s 25th anniversary in 2017 and its long history of developing market-based solutions in low- and middle-income countries around the world. It was open to students and faculty individually or on teams, and had to describe a dilemma or challenge faced by a company or organization related to creating, implementing, evaluating and/or disseminating market-based solutions in developing countries.

“By rolling out this competition globally, we not only invited case study submissions focused on WDI’s mission, but also created awareness of WDI and its 25-year history, ” said Sandy Draheim, manager of WDI’s case publishing and marketing. “Entrants included faculty and/or students from 10 countries representing over 40 different universities.”

The first round of judging was completed by an internal WDI team. However, the final winners were determined by an esteemed group of academic professionals which included Kim Bettcher, director of knowledge management at the Center for International Private Enterprise, and John Branch, Gautam Kaul, and Jordan Siegel, all professors at the University of Michigan’s Ross School of Business.

The second-place winners were Fernando Roxas and Andrea Santiago from the Asian Institute of Management in the Philippines. The pair wrote, “Milking the Future: DVF Dairy Farm Partners with the Filipino Farmer,” that explored whether Filipino farmers would be able to produce sufficient quantity and quality of carabao (water buffalo) milk to satisfy the demands of the DVF Dairy Farm customers.

In third place was “Chanderiyaan: Weaving Digital Empowerment into the Indian Handloom Industry,” by three professors from the FORE School of Management in India. The case, written by Bishakha Majumdar, Sriparna Basu and Shilpi Jain, studied a successful 15-year-old handloom enterprise as its founder considered making it an independent, self-sustaining social enterprise.

Uslay was awarded $3,500 for his first place win and donated the winnings to the “noble mission” of Roshni Rides, he said. The second place team won $2,500 and third place was awarded $1,000. Additionally, each winning case was professionally published by WDI Publishing.

Uslay knew about Roshni Rides because one of his students was the organization’s chief marketing officer. Uslay attended the local stage of the Hult Prize competition at Rutgers in 2016 when Roshni Rides won the award. He said he was proud to watch the team prepare for the Hult Prize competition, raise money to pilot their project and then win the global finals.

“They have a very moving story,” Uslay said. “Besides the pedagogical value of learning to deal with the real-life problems they are facing, I thought it would be inspirational for students who study this case to see that they too can create something that leads to a grand prize of $1 million and meet former President Bill Clinton at the U.N. in the process. In fact, Rutgers Business School has two teams in the global finals this year so I know I am right about the positive spillover effect of their story.”

Uslay said his case is unique in that it combines essential marketing planning issues with lean startup thinking. It also demonstrates what to do when you have key metrics and formulas but are unsure how to apply them in situations with imperfect information and high uncertainty. For Roshni Rides, Uslay said they could do a SWOT analysis, create a business model canvas and develop a five-year projection but they were doing a start-up in an environment where all the parameters were changing.

He said for his case, classroom discussions can be conducted at a high level or push deep into the details.

“It is a case that begs to be discussed both qualitatively and quantitatively,” Uslay said. “But at the end of the day it is a case of entrepreneurial marketing. How can we serve the underserved? Can we serve them well but profitably? Spoiler alert: yes.”

Photos courtesy of Roshni Rides.

An article published in the Stanford Social Innovation Review website and written by two WDI researchers showcases a framework for accelerating impact industries, those made up of profit-seeking, scalable businesses that also seek to create substantial social and/or environmental impacts.

Written by Colm Fay, who leads WDI’s Scaling Impact and Energy initiatives, and WDI Senior Research Fellow Ted London, this piece features a conceptual framework developed while working on a 2017 study for the Global Alliance for Clean Cookstoves (“the Alliance”). The Alliance is a public-private partnership hosted by the United Nations Foundation that aims to save lives, protect the environment, and improve livelihoods through access to clean cooking solutions. The study sought to identify which of the Alliance’s strategies worked, which were less successful, and the lessons that could be learned through its work to build a new global market for clean cooking solutions. The resulting framework is designed to help Impact Industry Accelerators (“IIAs”) such as the Alliance assess the current state of an industry, compare it to a desired future state, and prioritize and choreograph their strategic planning activities and investments accordingly.

After conducting research and interviewing Alliance leadership and its partners in Washington, D.C., Kenya and Bangladesh, Fay and London identified four interconnected strategies related to accelerating investment, mobilizing collective action, increasing profitability and enhancing impact. Fay said he hopes the insights developed from this work are applicable not only to the Alliance, but that they can be adapted for use by other IIAs that target low-income populations.

The Alliance has already begun to leverage the framework. It recently contributed to a new report published by the Alliance and Accenture which explores business model and financing challenges and opportunities to drive scale and sustainability in the clean cooking sector.

“The Alliance has contributed to significant progress towards establishing a viable clean cooking industry, and has learned much along the way, making this a fitting time to re-assess this growing space, and our organization’s role in it,” said Peter George, director of Enterprise Development and Investment at the Alliance. “The WDI research has helped us evaluate our priorities and will allow us to more effectively support businesses and other sector actors as we continue to work toward our shared goals.”

To achieve those goals, which include universal access to clean cooking solutions by 2030, the Alliance recognizes it must develop a sustainable industry that leverages mission-driven public resources to attract private sector innovation and capital. It is clear that while ambitious goals have been helpful in generating support for a cause, turning a vision of impact into reality can be challenging. This framework provides an approach that helps IIAs better identify, prioritize and choreograph their activities.

“We hope these insights lead to more constructive conversations between IIAs and their stakeholders that focus not just on milestones and deadlines, but on what needs to be done to accelerate an entire industry,” Fay said.

The Stanford Social Innovation Review is a quarterly magazine and website about social innovation published by the Stanford Center on Philanthropy and Civil Society at Stanford University.

Both images courtesy of Russell Watkins, Department for International Development (DFID).

Six U-M graduate students are participating in the 2018 WDI Global Impact Internship program.

When Rebecca Grossman-Kahn was in high school, she was a volunteer with Amigos de las Américas, a youth leadership and cultural exchange program that partners with Plan International, a global development and humanitarian organization. While an undergrad at Stanford University, she worked in Honduras and Nicaragua for the organization.

“I just loved it,” she said. “I loved living in a different place, I loved speaking Spanish.”

So when the Ross School of Business MBA candidate and University of Michigan Medical School student was looking to create her own summer internship, she reached out to several organizations. The first to respond was Plan International, which works to empower children – especially girls.

“They were interested in revamping their evaluation program and I knew WDI worked in performance measurement,” Grossman-Kahn said.

She pitched the partnership to WDI as a student-initiated internship and it was approved. In mid-June, she will head to Brazil to develop a survey tool Plan International will use to assess the impact of their programs. In addition to student-initiated internships, WDI also develops student summer opportunities along with its partners.

Grossman-Kahn is one of six U-M graduate students participating in the 2018 WDI Global Impact Internship program. The students represent the Ross School of Business, the School of Public Health, the College of Pharmacy, the School for Environment and Sustainability (SEAS) and the Medical School. They will work in Brazil, India, Indonesia, Kenya, Namibia and Nepal, and support the work of WDI initiatives in Education and its Entrepreneurship Development Center, Energy, Healthcare, Performance Measurement and Scaling Impact. All of the interns have met with their respective WDI initiative leaders and will continue to keep in touch once in the field.

Colm Fay, who leads WDI’s Energy Initiative, said he is interested in understanding more about access to energy for productive use because of the impact it can have in low- and middle-income countries. Fay will be working with graduate student Matthew Carney, who will be interning at Ecoprise, which designs, builds and installs clean energy products in Nepal for energy-poor communities.

“Matt’s work with Ecoprise will provide important learnings about how an innovative business model to provide energy for agricultural loads can impact rural livelihoods, and how the well-being of these communities can be enhanced through greater access to energy,” Fay said.

Fay also directs WDI’s Scaling Impact initiative and is working on a project in Kenya with intern Andrea Arathoon. He said Scaling Impact wants to develop tools and frameworks that help enterprises achieve sustainability at scale.

“Andrea’s experience with Jacaranda, an organization that is seeking both to scale its operations as well as replicate its approach through partners, will further our understanding of the strategies and resources that are necessary to design business models for scale,” Fay said. “Her work will also provide great insights on how enterprises measure performance in terms of both sustainability and impact, and how best to frame this for investors.”

For Grossman-Kahn, her summer in Brazil will not be her first trip to the country. She lived there while participating in a study abroad program as an undergrad and learned Portuguese. She is looking forward to going back and collaborating with a familiar partner.

Grossman-Kahn said she will split her time between doing high-level strategy work in an office in Sao Paulo and observing Plan International’s programs in rural towns.

“I’m really excited about working with Plan International again,” she said. “They are really mission driven. Everyone in the organization is passionate about the work they’re doing.”

Here are the all WDI interns and their projects:

Andrea Arathoon

School of Public Health

Jacaranda Health

Nairobi, Kenya

WDI Partner: Scaling Impact initiative

Jacaranda Health operates a maternity hospital where it sees more than 2,000 clients a month and wants to create East Africa’s first truly sustainable and scalable maternal health service delivery organization. It is partnering with 15 government hospitals to refine a model for improving quality of maternal healthcare in the public sector.

Andrea will develop the latest version of Jacaranda’s business model and debt/equity financing structure for its next round of investment. She also will assess market and business model opportunities for expansion, improve profitability in the hospital by evaluating new service lines, marketing and customer insights.

Mason Benjamin

School of Pharmacy

WDI & International Pharmaceutical Federation (FIP) Hospital Pharmacy Section (HPS)

Namibia

WDI Partner: Healthcare initiative

FIP is a global federation representing 3 million pharmacists and pharmaceutical scientists worldwide. The Hospital Pharmacy Section’s objectives are to further hospital pharmacy in all its aspects, including the needs of developing countries. FIP, in partnership with WDI, is establishing a collaboration with the University of Namibia School of Pharmacy to increase the capacity of hospital pharmacists in two pilot countries, Namibia and Pakistan, through in-country diagnostics and technical assistance. The summer intern will provide preliminary research on Namibia, which will then inform next steps and content design for this collaboration in pharmacy workforce development.

Mason will develop a landscape analysis of hospital pharmacy practices in Namibia, both at private and public hospitals, in support of a larger pharmacy workforce development goal.

Nadia Putri

Ross School of Business

East Bali Cashews

Bali, Indonesia

WDI Partner: Entrepreneurship Development Center (Education Initiative)

Founded in 2012, East Bali Cashews (EBC) sources sustainably grown cashews from nearby smallholder farmers and processes them in a factory located in a remote village in one of Bali’s poorest regions. Since its launch, the company has integrated various social missions in and around their cashew processing operations, including community improvement and women’s empowerment.

For her internship, Nadia will design a U.S. market entry strategy and actionable roadmap, develop sustainable quality and efficiency improvements and create a food production “best practices” guide. Additionally, in partnership with WDI’s Entrepreneurship Development Center, Nadia will develop a strategy to support EBC’s mission for women empowerment and develop a mini case study how they would achieve it.

Chris Owen

Ross School of Business and School for Environment and Sustainability

Michigan Academy for the Development of Entrepreneurs (MADE)

India

WDI Partner: WDI President Paul Clyde

The Michigan Academy for the Development of Entrepreneurs (MADE) is a U.S.-based nonprofit organization whose aim is to develop entrepreneurs in emerging economies. MADE was founded by the William Davidson and Zell-Lurie Institutes at the University of Michigan and Aparajitha Foundation in Madurai, India. MADE provides Entrepreneurship Development Organizations (EDOs) in emerging economies a repeatable, scalable, transferable and profitable service platform to develop entrepreneurs in their home countries.

For his project, Chris will Identify best practices of existing coaching programs in India and other emerging economies, conduct a needs assessment of entrepreneurs in Madurai and develop a framework and training curriculum for how coaches will be identified, on-boarded and trained. Chris’ work continues a succession of Ross School student teams who have worked with MADE since its launch in late 2017.

Rebecca Grossman-Kahn

Ross School of Business and University of Michigan Medical School

Plan International

Brazil

WDI Partner: Performance Measurement initiative

Plan International is a not-for-profit, non-governmental organization founded in 1937. It is a development and humanitarian organization that advances children’s rights and equality for girls through various programs.

For her internship, Rebecca will develop a tool to assess the social impact of Plan Brazil’s gender equality programs; develop a framework for evaluating impact of violence prevention and girls’ empowerment programs that can be adapted to other partner organizations and in other settings. In addition, Rebecca will also analyze Plan International’s program cost structure and provide recommendations for standardizing and cost savings.

Matthew Carney

Ross School of Business and School for Environment and Sustainability

Ecoprise

Nepal

WDI Partner: Energy initiative

Founded six years ago, Ecoprise designs, builds and installs clean energy products in Nepal for the underserved, energy-poor communities in order to create positive economic, environmental and social impact. Ecoprise recently started AgroHub, a pay-as-you-go service-based business model that aims to provide access to solar-powered infrastructure for remote underserved farming communities. These hubs provide farmers with access to equipment for irrigation, clean drinking water, food-processing and refrigerated post-harvest storage as a service, with ownership of equipment remaining with AgroHub or Ecoprise.

Matthew will develop a theory of change report and a business plan for Ecoprise’s AgroHub model in western Nepal.