A 2018 WDI MAP team in Ghana.

Carrie Boyle, a MBA student at Michigan’s Ross School of Business, hopes to work in philanthropy somewhere in the U.S. after graduation. But for a couple of weeks in March, she is excited to be traveling to India as part of the school’s annual Multidisciplinary Action Projects (MAP).

“Working in another country is something I may never get the chance to do again,” she said. “This will be my first time in India and the country really interests me.”

Boyle and her teammates will work with Michigan Academy for the Development of Entrepreneurs (MADE), a nonprofit institute established at Ross by the Zell Lurie Institute for Entrepreneurial Studies, in partnership with WDI and Aparajitha Foundations. MADE works with entrepreneurship development organizations in India to help entrepreneurs operating small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) succeed.

Boyle said she had some criteria when looking for MAPs that interested her.

“I wanted an opportunity to be on the ground having meaningful conversations with the people most immediately impacted by SMEs,” she said. “SMEs employ so many people and impact so many lives.”

Her teammate Shoko Wadano said she too is interested in working with SMEs, “which are very common in India.”

“I’m interested in how businesses mature in India,” she said. “I want to learn what pressures and impacts SMEs have in common, and what kind of value we can bring to them.”

WDI is sponsoring the MADE MAP project along with 10 others this year. MAP is an action-based learning course in which MBA students receive guidance from faculty advisors from WDI and Ross. Each project requires analytical rigor, critical thinking and teamwork. (Find out more about WDI’s MAP projects over the years here.)

After learning about their projects and conducting secondary research for several weeks, the student teams spend two to four weeks working with their organizations in the field.

David Butz

“The complementarities between the talents our students bring and what our sponsors need are sublime,” said David Butz, a WDI senior research fellow in the Healthcare sector who is an advisor on two projects. “Our students experience impact in brand new ways. Our sponsors learn, too, how disciplined management methods can yield dramatic innovations.”

Butz said he enjoys working with the student teams on MAP because it “poses such a unique challenge for both the students and their sponsor organizations, and forces us all to think big.”

“For me, the best achievements are tangible, direct and narrow but at the same time big and high-impact,” he said. “In our short time, can we help to break some key bottleneck, expedite a critical process pathway or otherwise liberate resources and expand capacity? Is the innovation scalable or replicable elsewhere? Do the students and organizations thereby feel empowered?”

Here is a summary of each WDI-sponsored MAP project:

Aravind Eye Care System – India

MAP Team: Rohan Dash, Sid Mahajan, Aman Rangan, Nik Royce

Aravind Eye Care System (AECS) is a vast network of hospitals, clinics, community outreach efforts, factories, and research and training institutes in south India that has treated more than 32 million patients and has performed 4 million surgeries since its 1976 founding.

AECS opened a tertiary eye care center in Chennai in September 2017 that will ultimately serve more patients than any other facility in the AECS system. The MAP team will formulate a detailed three-year strategic plan for Aravind Eye Hospital in Chennai.

CURE International, Inc. – Kenya, Ethiopia, Zambia, Uganda

MAP Team: Dominique James, Sarah Raney, Hannah Viertel, Olga Vilner Gor

CURE operates clubfoot clinics in 17 countries around the world, each tasked with helping children and families deal with the congenital deformity that twists the foot, making it difficult or impossible to walk.

For CURE, the student team will develop a strategic evaluation framework to assess opportunities for market entry and expansion building on global data.

Ghana Emergency Medicine Collaborative – Ghana

MAP Team: Benjamin Desmond, Benjamin Quam, Nicholas Springmann, Vishnu Suresh

The Ghana Emergency Medicine Collaborative aims to improve emergency medical care in Ghana through innovative and sustainable training programs for physician, nursing and medical students. The goal of the training programs is to increase the number of qualified emergency health care workers retained over time in areas where they are most needed.

The MBA team will formulate a detailed strategy to implement interoperable digital payment systems in Ghanian hospital emergency departments.

India Investment Fund – India

The India Investment Fund is working to become the first international, student-run fund at the Ross School of Business. Ross MBA students would be responsible for investing, managing and growing a real investment portfolio.

MAP Team: Charlie Manzoni, Patrick Riley, Queenie Shan, Sheetal Singh

The student team will conduct due diligence on Indian small- and medium-sized enterprises to assess viability for investments, and an appropriate financing instrument.

Infra Group – Ethiopia

MAP Team: Rin Chou, Chandler Greene, Yuki Ito, Brittany Minor

Infra Group is diversified international group with business units in financial services, industries and infrastructure development. Infra Group helps build a more prosperous society through global-scale business development with integrity as its top priority.

The MAP team will conduct due diligence on a group of small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), and recommend which ones to invest in and what amount to invest.

Lviv Business School & Ukranian Catholic University – Ukraine

MAP Team: Blake Cao, Emily Fletcher, Kelsey Pace, Adam Sitts

Lviv Business School and Ukranian Catholic University is a private educational and research institution in western Ukraine.

The student team will undertake a needs assessment of the small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) to determine if Lviv Business School should begin offering consulting services to these SMEs and if so, how those should be structured.

MADE – Poornatha/Aparajitha Foundations – India

MAP Team: Carrie Boyle, Lawrence Chen, Dillon Cory, Shoko Wadano

Michigan Academy for the Development of Entrepreneurs (MADE) is a nonprofit institute established at the Ross School of Business by the Zell Lurie Institute for Entrepreneurial Studies, in partnership with WDI and Aparajitha Foundations. MADE works with entrepreneurship development organizations in developing countries to give individuals operating businesses in these environments the knowledge and best practices they need to thrive.

The MAP team will develop an expansion plan for MADE in the southern Indian state of Tamil Nadu.

The Ihangane Project – Rwanda

MAP Team: Lauren Baum, Nadia Kapper, Paul Mancheski, Jason Yu

The Ihangane Project (TIP) empowers local communities to develop sustainable, effective, and patient-centered health care delivery systems that holistically respond to the needs of vulnerable populations. Partnering with Ruli District Hospital and its associated health centers, TIP is working to identify key strategies for improving health outcomes.

The student team will develop a business model to grow the ready-to-use therapeutic food that is used to treat severe, acute malnutrition.

WEEKEND MBA MAP PROJECTS

Awash Bank – Ethiopia

MAP Team: Matthew Campbell, Joshua Dodson, Joseph McCarty, Aman Suri

Awash Bank, a private, commercial bank, was established in 1995 and features more than 375 branches across the country.

The MAP team will develop a product that can provide capital to small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in Ethiopia by utilizing remittances already being sent back to that country. The students will work with the bank on all aspects of the loan product. They also will give the bank recommendations on how to monitor the loan and provide business support to SMEs that borrow from the fund.

Grace Care Center – Sri Lanka

MAP Team: Daniel Cady, Yizhou Jiang, Gerardo Martinez, Daniel Murray

The Grace Care Center (GCC) is a home to about 70 orphaned children that offers daycare services and vocational training. It also is home to several poor and displaced seniors, many of whom have chronic health issues such as hypertension and diabetes.

Past MAP student teams from the Ross School of Business developed a diabetic care center model for GCC. This year’s student team will examine the current model and make any needed updates and revisions.

International Clinical Labs – Ethiopia

MAP Team: Emily Mascarenas, Torre Palermino, Alexander Santini, Matthew Traitses

ICL was established in 2004 to provide quality laboratory service all over Ethiopia. ICL serves more than 240 health care centers throughout the country, and is expanding its service throughout Ethiopia.

The Ethiopian government is building its first medical waste incinerator facility outside the capital city of Addis Ababa and has committed to building seven more around the country. WDI is assisting a group of business managers with business plan advice who are interested in managing the business aspects of operating the incinerators. The MAP team will develop a proposal to be presented to the government later this year for the business managers to operate the incinerators.

It’s a new era when it comes to cooperation between some of the world’s largest corporations, governments and nonprofit organizations working together to address some of the most pressing social and environmental challenges.

So argued Tami Kesselman, an expert in impact investing and WDI’s Global Impact Speaker in January. Kesselman followed her University of Michigan campus discussion with a video interview at WDI’s offices.

Kesselman, the founder of Aligned Investing Global, works at the intersection of corporate, government, entrepreneurial and investor communities. Among the topics Kesselman addressed in the video include:

Kesselman’s WDI talk to U-M students gave them a behind-the-scenes look at how the business, government, philanthropic and investing communities overcame years of mistrust and misaligned priorities to begin a shift toward collaborative investments. She also discussed whether this large-scale, multi-sector collaboration in every part of the world is here to stay. And she also shared why she thinks businesses should consider the Sustainable Development Goals as a whole, rather than focus on individual ones.

Kesselman earned her bachelor’s degree in Industrial Relations at the University of Michigan with a triple minor in business, economics, and communications. She then went on to earn her Master of Public Administration degree at Harvard Kennedy School, with a dual concentration in business and government.

Improving reproductive health supply chains to boost access to family planning products in Mozambique. Educating senior managers from around the Baltics. Helping both investors and enterprises they support better measure impact in Latin America. Creating new MBA-level curriculum for universities in Papua New Guinea.

These partner projects are just a few examples of the work WDI performed around the world in 2018. Working with a robust set of private sector and nonprofit partners on a diverse number of projects, WDI effectively applied business skills in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) in impactful ways.

In all, WDI teams worked on more than 40 projects with more than 40 partners in more than 40 countries this past year that focused on our core consulting sectors—education, energy, finance and healthcare, as well as our management education programs, entrepreneurship development, measurement and evaluation services and the deployment of University of Michigan graduate students around the world.

“In 2018, I was impressed by the degree to which the Institute integrated the energy and talents of our staff, University of Michigan students and faculty leaders to address multiple challenges facing for-profit and non-profit organizations,” said WDI President Paul Clyde. “While most of these projects were in one of our key focus areas—Energy, Healthcare, Management education or Finance—many drew on expertise that cut across sectors or disciplines to deliver more complete solutions.”

WDI’s project work leveraged the knowledge and expertise of the Institute’s staff, its research fellows and faculty from the University of Michigan and other world-class higher education institutions to develop business solutions in LMICs. Additionally, WDI disseminated what it learned doing work in the field through published research reports, academic journal articles and notable blog posts. The Institute also contributed to U-M student and faculty enrichment by hosting several compelling speakers at the Ann Arbor campus.

Members of the LIFE project consortium visit a produce stand in Turkey and interviews the owner on how a green grocer sources his produce and his perspective on how he could potentially benefit from the LIFE Food Enterprise Center.

Our work in 2018 spanned the globe and included projects on a wide variety of topics and issues. Among the work, WDI launched a new consulting focus area in the energy sector, connected hundreds of students using virtual technology, developed a model to train nurses for a planned hospital in Ethiopia and trained refugees in the food industry in Turkey. Here are a few highlights from our project work this past year.

Throughout the past year, WDI has widely shared its research and field work a to a broader audience through a number of publications and online journals.

“Participating in the project to test the framework provided us a holistic understanding of poverty. WDI gave us the tools to guide decision-making and track progress towards broader development goals through data collection and analysis.”

—Mónica Varela, director of impact for the Clinton Giustra Enterprise Partnership

WDI intern Nadia Putri (pictured left)

A number of WDI employees penned blogs on their work or trends impacting their research that appeared on the Institute’s website.

In 2018, WDI hosted speakers as part of the the Institute’s Global Impact Speaker Series. While on campus, many of the speakers sat down for one-on-one interviews.

By Colm Fay

In early September in Delhi, India, the William Davidson Institute at the University of Michigan, and Miller Center for Social Entrepreneurship at Santa Clara University launched “Closing the Circuit: Accelerating Clean Energy Investment in India.” The event included round-table discussions with enterprises and investors on how they might implement some of the ideas presented in the paper.

One theme that emerged is that the challenges facing enterprises in the clean energy industry in India and the lessons they are learning are not unique to either the clean energy industry or, indeed, to India. In fact, some of the findings from our research reflect patterns that can be observed in any nascent industry. While the context of providing access to energy in India has its own unique characteristics, what we know about how industries develop might help guide investment and provide some clues as to what might come next.

After interviewing several energy access enterprises in the Energy Access India (EAI) program – funded by USAID from 2015-18 and implemented by Miller Center and New Ventures India – we observed a pattern emerging in terms of how enterprises evolved. There were three distinct stages of development: an early initial focus on a compelling value proposition; a stage of vertical integration where a company takes on additional supporting activities; and, a stage of moving these activities outside the enterprise through outsourcing partnerships to specialize around the enterprise’s core competencies.

In the “early focus” stage, enterprises develop a value proposition that targets a specific pain point for a specific customer segment. Hopefully they’ve co-created this value proposition with those customers, and it is something that creates value for them. Enterprises will likely see some early success as the product precisely meets the needs of these customers and they have the ability and willingness to pay for it.

Once enterprises seek to grow beyond this stage, they may be addressing a different customer segment, or operating in different geographic regions where the value proposition they’ve developed doesn’t fit quite as well. This may require widening their offering, through the addition of a consumer financing facility, developing new distribution models, additional after-sales service, etc. In a developed industry, partners would exist to undertake these activities. However, in nascent industries such as the clean energy industry in India, these partners often don’t exist, and enterprises must do it themselves.

It’s helpful to understand why these partners may not exist in the early stages of an industry’s development. Providing inputs or services in these contexts often require the creation of “specific assets” – investments that have extremely limited and specific uses. For example, if there is only one vendor of household appliances serving a particular region of rural India, developing an entirely new distribution network for household appliances as a standalone business is unlikely to be a profitable business. At the price that the distributor would have to charge to cover their cost, it would be cheaper for the vendor to build this capability themselves.

However, enterprises often can’t continue to be experts in everything as they grow. For most enterprises, the next stage of growth is going to require focusing on their core competencies, executing at higher volumes that generate economies of scale and having partners optimized around providing inputs or supporting services. If the enterprise has been successful in demonstrating the possibility for commercial viability, it is possible that others have recognized the opportunity and have entered the market. Now providers of supporting inputs and services look at the market and see multiple potential clients and that mitigates the risk of their investments.

Simpa Networks is a great example of this type of evolution. The enterprise started out as a provider of solar home systems. As it developed its distribution network, it launched consumer financing products that enabled a greater number of customers to purchase the product. It also began providing a range of appliances that increased the use of energy, thereby increasing demand for its core product. Through this process, the enterprise has become an expert in understanding consumer needs and providing solutions to meet these needs through an extensive distribution network that reaches the last mile. Rather than replicating this integrated model everywhere, it now seeks to optimize its strategy around this core competency to become the leading distributor of household appliances to the last mile regardless of where the energy to power them comes from. In effect Simpa Networks is outsourcing the electricity generation component of its business. This kind of specialization only becomes possible when there is a sufficient number of energy providers in the market. Because they are focused only on electricity generation, and are serving smaller geographic areas, they are able to do so more efficiently than Simpa Networks can. This demonstrates another interesting twist – what may have been the subject of an enterprise’s early focus may not continue to be its core competency as it grows.

This evolution from early focus to vertical integration to specialization is nothing new. It is exactly how firms operate in nascent industries. While these models can provide guidance for enterprises and help inform their strategies, it is also important for impact investors and the development community to recognize these dynamics of how an industry matures. It can be tempting for these stakeholders to focus on finding the next new technology, the next business model innovation, or a new financing vehicle that will unlock sustainability and scale. What isn’t as obvious is investing in business to business enterprises across the value chain that facilitates specialization and optimization or improvements in the legal environment that make it easier to enforce contracts between partners. In our discussions with investors in the clean energy space in India, we noted that several are beginning to look at whether their investments are catalytic for the industry, as well as representing good investment deals.

This was a topic of a number of conversations at SOCAP 2018 in San Francisco in October. As part of the panel discussion “Moving from Good Impact Deals to Great Systems Change,” Clara Miller of the Heron Foundation described the importance of supporting efforts like the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board. Neil Yeoh of Echoing Green encouraged investors that wish to see greater pipeline, to also invest in the plumbing.

In “Closing the Circuit,” we also identify some broad categorizations of the Energy Access India (EAI) portfolio companies in terms of the business models they are pursuing. While the distinction between business models may be fuzzy, we saw three distinct patterns emerge; pure-play energy providers, complementary products and services and integrated productive use.

Pure-play energy providers are focused on the generation of electrons at volumes that are profitable. This may mean providing a combination of solar home systems, rooftop solar and solar pumps. These companies leverage economies of scale across these different customer segments to reduce costs and become commercially viable. For example, Argo Solar provides rooftop solutions for profitable customer segments including commercial and industrial customers. It also engages in government tenders for solar pumps in rural markets and drives economies of scale across both markets.

Complementary products and services enterprises focus on developing a basket of products, which may include both the generation and use of electrons. These companies leverage economies of scope to reduce costs and become commercially viable. This means that production of a second product can be done so more efficiently because the company is also producing the first product. Grassroots Energy (GRE), for example, is a biogas production company in the EAI portfolio. It uses animal waste to produce gas that is used as a backup energy source for mini-grids rather than diesel generators. To do this it needs to collect animal waste from local farmers. The residue that remains after the production of biogas, with some addition of nutrients, is an effective fertilizer. GRE can produce this fertilizer product much more efficiently than a standalone business because it already collects the waste and processes it through bio-digestion in the course of generating energy.

Integrated productive use enterprises provide access to energy, but also focus on promoting and facilitating productive use of that energy. This is typically required in contexts where ability to pay is low, and productive use of energy has economic benefits that increase customers’ ability to pay. Without productive use to drive up utilization of the energy generation assets, typically mini-grids, these businesses would not be viable. These models require deep learning about how such communities operate, their energy needs, and how to identify and nurture productive use applications. Companies implementing this model leverage economies of learning to reduce the cost of each subsequent implementation.

Mlinda is an example of this model. It installs mini-grids that provide a higher-quality and more reliable source of energy for rural communities in Jharkhand, India. It also invests significant effort in helping the local community to develop micro-enterprises, such as producing mustard oil, rice hulling and poultry production. Of course, this is only economically productive if there is a market, and so Mlinda also creates market linkages to enable the community to sell these products. As it replicates this model, Mlinda is developing the knowledge assets that will enable it to reduce the cost of community engagement over time.

These models and the associated economies of scale, scope, and learning might sound familiar to anyone who has taken an MBA strategy class. Hagel and Singer cover similar ideas in “Unbundling the Corporation.”

We spend a lot of time focusing on the unique aspects of working in resource constrained environments. Indeed, it is critically important to understand the inherent nuances. However, these examples demonstrate that despite the vast differences in context, some of the business principles we are familiar with in other industries can be observed and that creates the possibility that we might be able to look to history, and to other industries, to anticipate what might happen next in these markets. Further, it may help entrepreneurs, investors, funders and practitioners to gain a deeper understanding of what they should do next to help accelerate these industries to a point where they are mature, competitive and can attract sufficient commercial capital to become self-sustaining.

Colm Fay is a program manager leading WDI’s Energy Sector focus area.

Download PDF of the report

The author, left.

This blog was written by 2018 WDI summer intern Nadia Putri, an MBA candidate at the University of Michigan’s Ross School of Business. It originally appeared on NextBillion.net, an initiative of WDI.

By Nadia Putri

In 2012, Lasmini began working as a daily laborer at East Bali Cashews (EBC) and has worked her way up to be the factory’s kitchen production coordinator. Her path was not without obstacles. Many Balinese women at the base of pyramid, especially in a remote village like Karangasem, have limited access to education and employment opportunities. More than 20 percent of women in Karangasem are illiterate. In addition, of those who are employed in the formal sector, the number of women employees are between 50-75 percent of men. Many women stay unemployed at home or work as informal laborers in agriculture, maintaining a small plot of land or a few animals.

Lasmini was one of the few who completed high school. However, lack of opportunity in the village left her unemployed. Her husband’s income alone was not enough for the family. She helped her mom to make and sell canang sari, daily offerings made by Balinese Hindus to thank God in their prayers. But this did not come close to fulfilling their daily needs. Then the opportunity at EBC came along.

EBC is a vertically-integrated social enterprise specializing in cashew products. It operates a processing facility in remote Desa Ban (Ban Village), Karangasem, one of the poorest regions in Bali, Indonesia. In 2012, Aaron Fishman travelled to Karangasem as a health care volunteer. He was amazed by the beauty of the region, but was struck by the poverty of its cashew farmers. He sought out local partners and started EBC, a social enterprise that combines environmentally sustainable business practices with its mission of community development and women’s empowerment.

EBC capitalizes on the opportunity to process cashews domestically in Bali, rather than the more common practice of shipping the raw product overseas for processing. Each day, EBC processes, on average, about 800 pounds of raw cashews, peeling and preparing them for snack production. (This doesn’t include other finished products, which they also package for snack goods). In addition, EBC emphasizes hiring local talent, especially women, because women’s empowerment and economic development are closely related. The factory currently employs more than 400 people, where 80% of them are women from local Karangasem area. The company’s leadership wants to ensure that what they are building in Desa Ban will lead to the community’s overall prosperity.

As a William Davidson Institute MBA summer intern at EBC’s factory, I had the opportunity to interact with many female employees like Lasmini. Some had successfully ascended to supervisory positions, while others have stayed in the same position since their first day. However, one common thread is that they all have benefited from management’s initiatives in providing them with training opportunities.

For instance, Putu started as a cashew-shelling laborer. She only completed elementary school. However, her limited formal education did not discourage her supervisors from training and promoting her to be the first woman mechanic at the EBC factory. I regularly saw her armed with with a toolbox and steel-toed boots, working on machines in need of repairing.

The company also aims to provide equal education opportunity for all levels of employment. For those in the lower level, EBC enrolls employees in NGO-ran weekend classes that prepare them for elementary, middle or high school final examinations, depending on the employee’s needs. For employees who are at staff level or above, EBC offers various in situ training during work hours, ranging from Excel to English.

Providing continuous learning opportunities for employees, in turn, increases their work motivation. As one of the employees told me, “I feel very fortunate to work here and the environment is not like a typical job. Here, it feels like I’m going to college while getting paid at the same time. There’s always something new for me to learn.”

I spent the last two weeks of my internship at EBC providing training and facilitating workshops for supervisors at the factory. Twelve out of 17 training participants were women, some of whom had been recently promoted to supervisor roles, and others who had been supervisors for some time. This shows EBC’s implementation of their women’s empowerment mission: They not only hire women to work as manual laborers, but encourage them to take on leadership roles and further responsibilities.

One example is Wayan, who became coordinator of the peeling area in 2016. Her journey there was not smooth. When her supervisor gauged her interest in becoming a coordinator, she was scared. She had never led people before and felt ashamed of her middle school degree. But, after continuous encouragement, she took on the challenge and has been the area’s coordinator for the past two years.

Wayan’s story shows that leading others often does not come naturally for these employees because they have never had such responsibility before. But EBC keeps pushing the boundaries by providing them with support and setting them up for success once they become a leader. In addition, the company has women in their upper management team, such as General Manager and Head of People Operations, that become role models for the factory employees.

Achieving goals to empower women in a village chock-full of patriarchal tradition is not without hurdles. Though EBC provides opportunities for its employees to grow, at times these opportunities are ignored. In Karangasem, society expects a woman’s first priority should be her family. They fully accept the concept of working mothers. However, this should not come at the expense of their responsibilities at home. After work, many women at EBC will return home and still have to collect hay for their cattle. Some women might turn down promotions or training opportunities due to the additional time commitment. Yet, I’ve heard stories where the household dynamic eventually changed for some of them. Husbands started pitching in to do chores that used to belong solely to women. But such change did not happen overnight. Thus, as EBC work towards fully realizing its goal of equal opportunity for women, its managers need to keep in mind the personal challenges that these employees face everyday. Because once she overcomes these challenges, she can do anything. Lasmini told me once: “I never thought I could get here. But here I am and I can dream again of a better life for my children.”

Note: This article originally appeared on PYXERA Global. It is re-published here with permission.

In 2017, the William Davidson Institute at the University of Michigan collaborated with the Global Alliance for Clean Cookstoves (the Alliance) to assess the lessons learned so far on the Alliance’s journey to accelerate the clean cookstove industry. This blog is based on the article “Accelerating an Impact Industry: Lessons from Clean Cookstoves” first published by the Stanford Social Innovation Review on June 1, 2018.

Announcing the launch of the Alliance in 2010 at the Clinton Global Initiative, then Secretary of State Hillary Clinton remarked that the Alliance would “work toward the goal of 100 million homes adopting new clean stoves and fuels by 2020. Our long-term goal is universal adoption all over the world.” By bringing together leaders from both the public and private sectors, the Alliance aimed to build a clean cookstove industry that could deliver this vision.

For decades, the development community has been investing in programs that seek to harness the power of business to address social challenges. Not only has this meant investing in private enterprises, but also investing in developing the policies, information, institutions and infrastructure that define the industries in which these enterprises operate—what we call impact industries.

Of course, before the Alliance launched there were many efforts to invest in the clean cookstove industry. But like many impact industries, these were fragmented efforts that operated independently of each other and lacked an integrated vision. This resulted in a lack of investment and coordination, and market environments that make it challenging for enterprises to be profitable – never mind reach scale. Rather than being another independent effort, the Alliance was formed to be what we term an Impact Industry Accelerator (IIA)—an entity charged with catalyzing an entire impact industry.

Almost three billion people around the world still cook over open fires or with biomass such as wood, charcoal and dried animal dung. The stoves they use are inefficient, and they expose the user to a variety of toxic gases, chemicals and airborne particulates. These pollutants cause a variety of health issues, including pneumonia and heart disease, and disproportionately impact women and girls who do most of the cooking. Apart from the health impacts, these inefficient stoves and biomass fuels have impacts on climate change and the environment.

The Alliance aims to better understand the links between improved cooking technologies, and changes in these negative outcomes. It works globally to advocate for improved standards for cookstoves and fuels, to promote investment in enterprises that provide them, and to educate and inform consumers about their benefits. At the country level, it works with local governments, non-governmental organizations and the private sector to develop and execute plans to achieve these objectives.

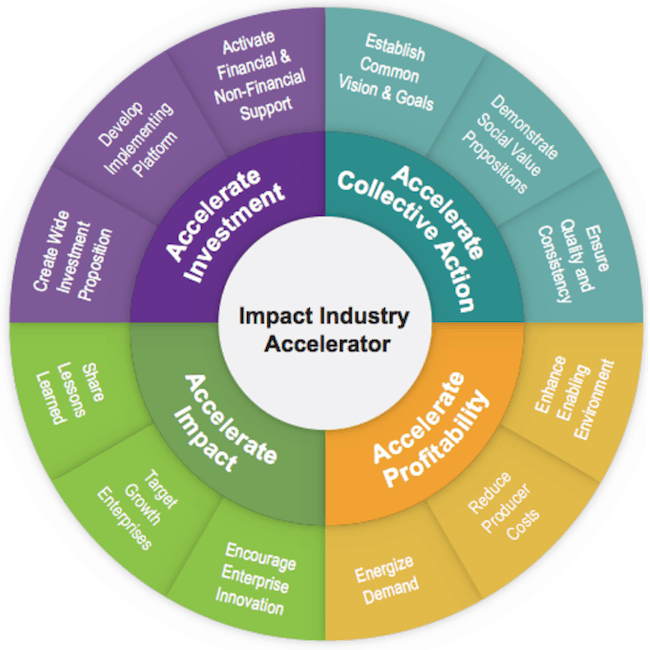

For this research we interviewed Alliance staff and partners in Washington, D.C., Kenya and Bangladesh. In these discussions we talked about what the Alliance has done to accelerate the clean cookstove industry, but also things that the Alliance and other organizations have not addressed yet. This led us to identify four different, but interconnected stages of impact industry acceleration—accelerating investment, collective action, profitability and impact. The Alliance didn’t implement these strategies sequentially, as there were overlaps and iterations. Indeed, the Alliance found itself investing in activities from all four stages at any given time, albeit at different intensities.

Four Acceleration Strategies for the Clean Cookstove Industry

1. Accelerate Investment

The Alliance did three key things to mobilize resources for the clean cookstove industry:

2. Accelerate Collective Action

Given the multitude of prior and current efforts to develop the clean cookstove industry, the Alliance had an important part to play in coordinating a collective strategy for action:

3. Accelerate Profitability

The Alliance aimed to increase access to clean cookstoves and fuels through healthy markets, and has done three important things to help enterprises achieve profitability:

4. Accelerate Impact

To increase impact and scale, the Alliance has focused on key steps to encourage innovation, scale and learning:

By 2017, the Alliance had experienced important successes in accelerating investment and collective action, and its efforts focused on this latter stage. As it looked to the future, it sought to place greater emphasis on accelerating profitability and impact, and on the creation of a healthy market for clean cookstoves and fuels. However, this shift will likely require new thinking in terms of internal capabilities, as well as new external partnerships. This framework provides a roadmap for that transition.

While we developed this framework and roadmap for the Alliance, we think these principles can be of benefit to other IIAs in similar impact industries. Frameworks such as these can facilitate improved strategies and approaches that increase the probability that IIAs can turn their visions of impact into reality.

This article is part of a series on “solvable problems” within the context of the UN Sustainable Development Goals. The Global Engagement Forum: Live takes place this October 10–11, 2018, bringing together leaders from across the private, public, and social sectors to co-create solutions and partnerships to address four urgent, yet solvable problems—closing the skills gap in STEM, reducing post-harvest food loss, ending energy poverty, and eliminating marine debris and ocean plastics. Learn more about the Forum here.

Image courtesy of Russ Keyte.

How data shaped the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals, how it is transforming local and global problem-solving, and the risks posed by a policy makers and a public increasingly skeptical of data will be the topic of a Oct. 1 talk co-sponsored by WDI and the Center for Value Chain Innovation.

Daniella Ballou-Aares, partner at the global advisory firm Dalberg Advisors, will give the talk, “Data Innovation for Global Problem Solving: Promise and Peril” beginning at 5 p.m. in Room R2230 at the Ross School of Business. It is open and free to the public.

Ballou-Aares will discuss if data innovations can transform how the world responds to the biggest social, economic and environmental challenges, and if data is able to bring nations, companies, and citizens together for a common cause. Conversely, she will examine whether the ability of data to influence decision-makers is on the decline, and if the impact of data innovations will be unable to address the world’s most significant development challenges.

Ballou-Aares will discuss if data innovations can transform how the world responds to the biggest social, economic and environmental challenges, and if data is able to bring nations, companies, and citizens together for a common cause. Conversely, she will examine whether the ability of data to influence decision-makers is on the decline, and if the impact of data innovations will be unable to address the world’s most significant development challenges.

Ballou-Aares was a founding partner that grew Dalberg from start-up to a global group of businesses that now has 17 offices across Africa, Asia, Europe and the Americas. She served as senior advisor for development to two U.S. Secretaries of State during the Obama administration, supporting the secretary’s role as board chair of the Millennium Challenge Corp., a multibillion-dollar fund that invests in infrastructure and other large-scale projects in newly-emerging economies. She also guided data-driven targeting of the $6 billion annual HIV/AIDS budget to reach millions with treatment and helped secure a 193-country agreement on the Sustainable Development Goals. She returned to Dalberg in 2017.

In 2014, she was selected as a World Economic Forum Young Global Leader and currently serves on the group’s Advisory Council. She is a member of the Council on Foreign Relations. Prior to serving in government, Ballou-Aares was at Bain & Co. and advised financial services, private equity, telecom, healthcare and consumer product firms in the U.S., U.K. and South Africa. She holds an MBA from Harvard Business School, a master’s degree in public administration from Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government and a bachelor’s degree in Operations Research and Industrial Engineering from Cornell University.

Top photo by Mika Baumeister on Unsplash

By Dan DeValve

The decision by small and medium enterprises (SMEs) in emerging economies to enter an international market is a key step in their maturation. For some SMEs, the move is necessary for survival in a competitive local economy, while for others it’s a logical next step for a successful and growing organization.

Kim Ian’s Dairy Delights is an excellent example of how a locally successful business in an emerging economy, in this case, the Philippines, approaches the decision to transition to the regional or international market. In 2015, I traveled to the Philippines and visited the town of Los Baños, home to many agribusinesses and located near the capital city of Manila. One of the town’s successful small businesses, Kim Ian’s Dairy Delights, had rapidly grown its production of goat milk-based cream cheese. It now faced a decision between scaling up the business to reach supermarket chains in Manila, or remaining in the much smaller niche market in Los Baños. The business owner recognized that expansion of the business would require reallocation of resources to pay for marketing and logistics, significant financial investment and risk, and a strategy for healthy growth of the company. Despite the risks, ultimately the namesake owner decided that their success hinged on a transition to the larger Manila market.

“Foreign market entry is considered as a key strategy to grow and survive over longer periods of time for SMEs,” according to a recent study on Bangladeshi SMEs in the International Marketing Review. In emerging economies with vibrant entrepreneurship sectors, such as the Philippines, the decisions made by these business leaders are instructive and can be illuminating for SMEs in other emerging economies.

While entering the export market has clear benefits, it is a major risk for a small business and can easily result in failure. As key factors of success, a recent study in the Journal of World Business stressed the importance of international business experience on the part of the SME owner, the strength of the home country’s institutional support for SMEs, and whether the SME is using the proper business model. If they have the advantage of institutional support, such as the local government or a business incubator, business owners can also utilize a “learning-by-exporting” model to make the transition, as highlighted in a previous NextBillion post.

A selection of three recent case studies published by WDI Publishing, part of the William Davidson Institute, highlights several issues commonly faced by Philippine SME owners as they consider a move to the international market. These three cases, which are available for free, were among a total of 94 published as part of a four-year project focused on training university faculty in the Philippines on how to teach and write business case studies. WDI implemented the project, in partnership with RTI International and the United States Agency for International Development (USAID).

A business case study is a documented analysis of a real-life business scenario, typically one in which the protagonist must make a crucial decision affecting the success of the business. As a teaching tool, cases provide students with “real-life” experience in decision-making and strategic thinking. As Philippine faculty engaged with a local business and identified a dilemma to feature in their cases, we noticed many focused on whether or not SMEs in the Philippines should enter international markets.

A common theme runs across these three cases. Each business is established in the domestic market with varying degrees of success, and each owner recognizes the advantages to be gained in exporting. Despite the potential benefits, the business owners must also consider the risks, especially adjusting an existing business model and scaling up production capacity to meet the demands of a new market.

Because the case studies were published in 2016 and 2017, WDI was able to review the various decisions ultimately made by these business owners and the ensuing results:

As this view inside three organizations showcases, SME owners can find it difficult to make the transition from domestic to international markets due to a lack of business experience. However, as illustrated in the cases of IPMC and REFMAD, government support for SMEs during this process is crucial. It can include assistance, such as the coordinating of trade fairs to help business owners make new connections, entrepreneurship training programs to provide business owners with the tools needed to scale a business, or even simple promotion of the business to potential customers.

As in the case of GFCP, if the business expertise, proper business model and ability to scale up production are absent, and the business has little to no external support, the idea of entering the international market remains only a dream.

Note: This article was written by Daniel DeValve, a senior project manager for grants management at WDI. The article originally appeared on NextBillion, which is managed by WDI.

Photo by I Travel Philippines via Flickr

An article published in the Stanford Social Innovation Review website and written by two WDI researchers showcases a framework for accelerating impact industries, those made up of profit-seeking, scalable businesses that also seek to create substantial social and/or environmental impacts.

Written by Colm Fay, who leads WDI’s Scaling Impact and Energy initiatives, and WDI Senior Research Fellow Ted London, this piece features a conceptual framework developed while working on a 2017 study for the Global Alliance for Clean Cookstoves (“the Alliance”). The Alliance is a public-private partnership hosted by the United Nations Foundation that aims to save lives, protect the environment, and improve livelihoods through access to clean cooking solutions. The study sought to identify which of the Alliance’s strategies worked, which were less successful, and the lessons that could be learned through its work to build a new global market for clean cooking solutions. The resulting framework is designed to help Impact Industry Accelerators (“IIAs”) such as the Alliance assess the current state of an industry, compare it to a desired future state, and prioritize and choreograph their strategic planning activities and investments accordingly.

After conducting research and interviewing Alliance leadership and its partners in Washington, D.C., Kenya and Bangladesh, Fay and London identified four interconnected strategies related to accelerating investment, mobilizing collective action, increasing profitability and enhancing impact. Fay said he hopes the insights developed from this work are applicable not only to the Alliance, but that they can be adapted for use by other IIAs that target low-income populations.

The Alliance has already begun to leverage the framework. It recently contributed to a new report published by the Alliance and Accenture which explores business model and financing challenges and opportunities to drive scale and sustainability in the clean cooking sector.

“The Alliance has contributed to significant progress towards establishing a viable clean cooking industry, and has learned much along the way, making this a fitting time to re-assess this growing space, and our organization’s role in it,” said Peter George, director of Enterprise Development and Investment at the Alliance. “The WDI research has helped us evaluate our priorities and will allow us to more effectively support businesses and other sector actors as we continue to work toward our shared goals.”

To achieve those goals, which include universal access to clean cooking solutions by 2030, the Alliance recognizes it must develop a sustainable industry that leverages mission-driven public resources to attract private sector innovation and capital. It is clear that while ambitious goals have been helpful in generating support for a cause, turning a vision of impact into reality can be challenging. This framework provides an approach that helps IIAs better identify, prioritize and choreograph their activities.

“We hope these insights lead to more constructive conversations between IIAs and their stakeholders that focus not just on milestones and deadlines, but on what needs to be done to accelerate an entire industry,” Fay said.

The Stanford Social Innovation Review is a quarterly magazine and website about social innovation published by the Stanford Center on Philanthropy and Civil Society at Stanford University.

Both images courtesy of Russell Watkins, Department for International Development (DFID).

University of Michigan students chat during an M2GATE virtual exchange session.

A Washington, D.C. forum on the positive impacts virtual exchange programs can have on communities and young people worldwide included a panel discussion featuring Amy Gillett, vice president of WDI’s Education initiative.

The forum, “Inspiriting Civic Engagement through Virtual Exchange,” was sponsored by the Stevens Initiative and hosted by the Aspen Institute. It was held May 17-18. The panel discussion is featured below and begins at the 1:23:10 mark.

Gillett discussed WDI’s work this year with the Stevens Initiative on the MENA-Michigan Initiative for Global Action Through Entrepreneurship (M²GATE) program. For the first two cohorts, WDI recruited 111 students from three Michigan universities ― University of Michigan, Wayne State University and Eastern Michigan University ― and 223 of their peers from the participating Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region countries of Egypt, Libya, Morocco and Tunisia. The third and final cohort began May 25 with 60 Michigan students and 151 MENA students enrolled.

For the project, the Michigan-based students were paired with their Middle East counterparts to find entrepreneurial solutions to social challenges in the MENA region. Working virtually, teams of six developed social entrepreneurship projects and accompanying pitches over an eight-week period. Guiding them along the way were instructors, mentors, and successful entrepreneurs from MENA and Michigan. The teams coordinated times for virtual group work and produced a pitch video as a final assignment.

Gillett was joined on the panel by Jennifer Chen of World Learning and Victor Eno of Florida A&M University, leaders at two other organizations that also implemented virtual exchange programs in partnership with the Stevens Initiative. The three discussed why it is important for young people to be active participants in their communities, what they can learn about civic engagement from their global peers and how virtual exchange programs can advance participation.

“This program fundamentally changes participants’ point of view on their role in society by helping them realize that they can be the ones to address issues in society instead of waiting for the government or some other entity to take action, Gillett said. “Some of our participants are starting to refer to themselves as ‘changemakers’ and I think that’s an apt description.”

The Stevens Initiative is an international effort to build global competence and career readiness skills for young people in the United States, the Middle East and North Africa; it is funded by several public and private donors including the U.S. Department of State and the Bezos Family Foundation.